Without the brain, the human body would be a collection of tissue with no function. The digestive system would be a cesspool of corrosive chemicals, the respiratory system a collection of empty passageways. The heart would not beat.

According to antranik.com, the bones surrounding the brain, collectively known as the skull, protect the brain from harm. Tissue, known as meninges, and cerebrospinal fluid provide extra cushioning to prevent the brain from colliding with the hard skull.

Despite natural protective measures in place, the brain can still be injured. In cases of excessive trauma, concussions occur. According to Dr. Andrew Hunt, a sports medicine specialist at Illinois Bone and Joint Institute (IBJI), the trauma that induces concussions interrupts the connections of a healthy brain.

“Concussions alter the normal functioning of the brain due to the mechanical injury[….] There’s damage that interferes with how the neurons and the brain communicate,” Hunt said. “Every concussion[…] can affect how people normally perceive [and] think.”

According to Hunt, concussions pose a particular threat towards young people because of their developing brains.

“In kids, [concussions] can be especially problematic because they’re especially susceptible [and] they are in the process of learning, and a concussion can interfere with their ability to do that,” Hunt said.

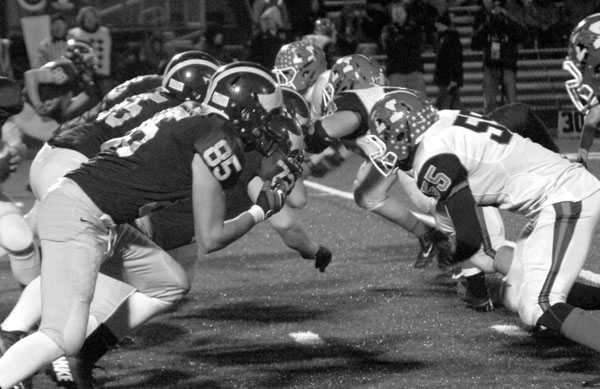

Concussions are naturally more prevalent when the brain is travelling at high speeds and experiencing collision forces. This puts athletes, who are frequently in motion, at particular risk. Contact sports, especially ones like football, are particularly conducive to the head trauma that induces concussion.

The prevalence of concussions has been relatively constant throughout sports history. Despite this, Dustin Fink, an athletic trainer in Shelbyville, IL. who runs theconcussionblog.com, believes that people have only just begun to realize the scope of what is happening.

“I think it’s a generational thing[…] [Concussions] were happening but we didn’t know what was going on until [we found out] what we know now,” Fink said.

Hunt attributes raising awareness to prolific cases involving ex-NFL players. These have prompted people to take concussions more seriously as well.

“I think, unfortunately, it’s been the NFL experience with some of the fairly high-profile findings from recent suicides,” Hunt said. “Autopsy studies that have shown that repetitive, long term concussions can lead to serious pathology on the order of Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s disease.”

Hunt reciprocates this viewpoint, explaining why diagnoses have become more frequent over recent years.

“I think we’ve done a much better job over the last ten or fifteen years in recognizing the severity and extent of the injury,” Hunt said. “I think a lot of that has come about with the availability of neuro-psych testing that previously was unavailable to groups and organizations other than professional sports teams.”

NFL players are not the only people at risk for long-term results of concussion. Fink believes that anybody with a long history of concussion is predisposed for mental issues in the future, something he believes he has been affected by himself.

“The main thing that I’ve seen [are] the emotional aspects, and the long term effect there is, [including a] learning disability,” Fink said. “It’s not always common, and there [are] lots of people who’ve had head injuries and done well. I’ve had 11 [concussions] myself and I carry a master’s degree, and it’s not that I can’t learn, but I do struggle with things like depression and anger management at times, and I wasn’t like that five, ten years ago, but I am now. There could be a lot of factors, but those are the things we need to be wary of.”

While the long-term effects are the most drastic, the short-term effects are nothing to scoff at. Taylor Bielanski, sophomore hockey player, has suffered four concussions and says that concussions have had a severe impact on his life.

Bielanski says that his repetitive concussions have led to “kind of a slower thought process, tougher doing homework and a lot of trouble focusing.”

In response to a growing number of situations like Bielanksi’s, the Illinois Highschool Association (IHSA) has made attempts to curtail the number of concussions and keep athletes out of danger.

The new policy requires that coaches “shall be educated about the nature and risk of concussions and head injuries”, “Shall immediately remove from participation/competition any athlete who is suspected of sustaining a concussion or head injury”, and “Shall not allow an athlete who has been removed from play because of a suspected concussion/brain injury to return to play until the athlete has received written clearance from a physician”.

Despite these efforts, players still often play through head injuries. Hunt equates this to an overall lack of awareness among athletes.

“Unfortunately, many high school kids don’t appreciate the severity [of concussions], want to play and will tell you anything they need to get back on the field,” Hunt said. “[Recognizing concussions] becomes a difficult task where the value of experience is huge.”

Thus, when kids do suffer concussions, the responsibility is put on the athletic trainers to recognize if a kid is faking health. According to Fink, this is extremely difficult because there is no objective field test for concussions.

“Kids need to understand [the risk], they have to be honest, because it’s so subjective as an athletic trainer,” Fink said. “I can’t tell if a kid is dizzy or not unless he is [visibly] stumbling around[…] so it’s up to them to tell me.”

Head injuries are intrinsic to sports like football, hockey and lacrosse. No matter the technology or rule changes implemented, people will get hit in the head because of the fast-paced and violent nature of sports.

With that being acknowledged, Fink believes that with rising awareness, full-contact sports like football will be approached differently in the coming years.

“The sport as we see it [may change],” Fink said. “I see an increase in flag football; I see an increase in alternatives with less collisions for younger athletes. I think we’re at the highest level for tackle football right now.”

Hunt agrees that football is on the verge of changing, but does not expect football to fade to the extent boxing, another dangerous sport, did during the 20th century.

“I think it’s going to be an ongoing issue that develops over time,” Hunt said. “I don’t ever see football going away, but over the course of time with increasing numbers [of head injuries] maybe there might be rule changes. It’s tough to say. I don’t think it’s anywhere on the order of boxing [in terms of riskiness], but I don’t think we’ve ever allowed kids to box.”

According to Fink, as long as there are sports, there will be risk for head injuries.

“The problem with concussions in football or any[…] sport or activity[…] is [that] the brain is just floating inside the skull,” Fink said. “Even if we put a helmet around a head, it doesn’t impede the brain from sloshing around and causing the issues. The linear forces that create skull fractures and major brain bleed are definitely attenuated by helmets, and that’s why they’re in place, but what the helmets don’t do, and what they can’t do, is stop the brain from rattling inside the skull.”