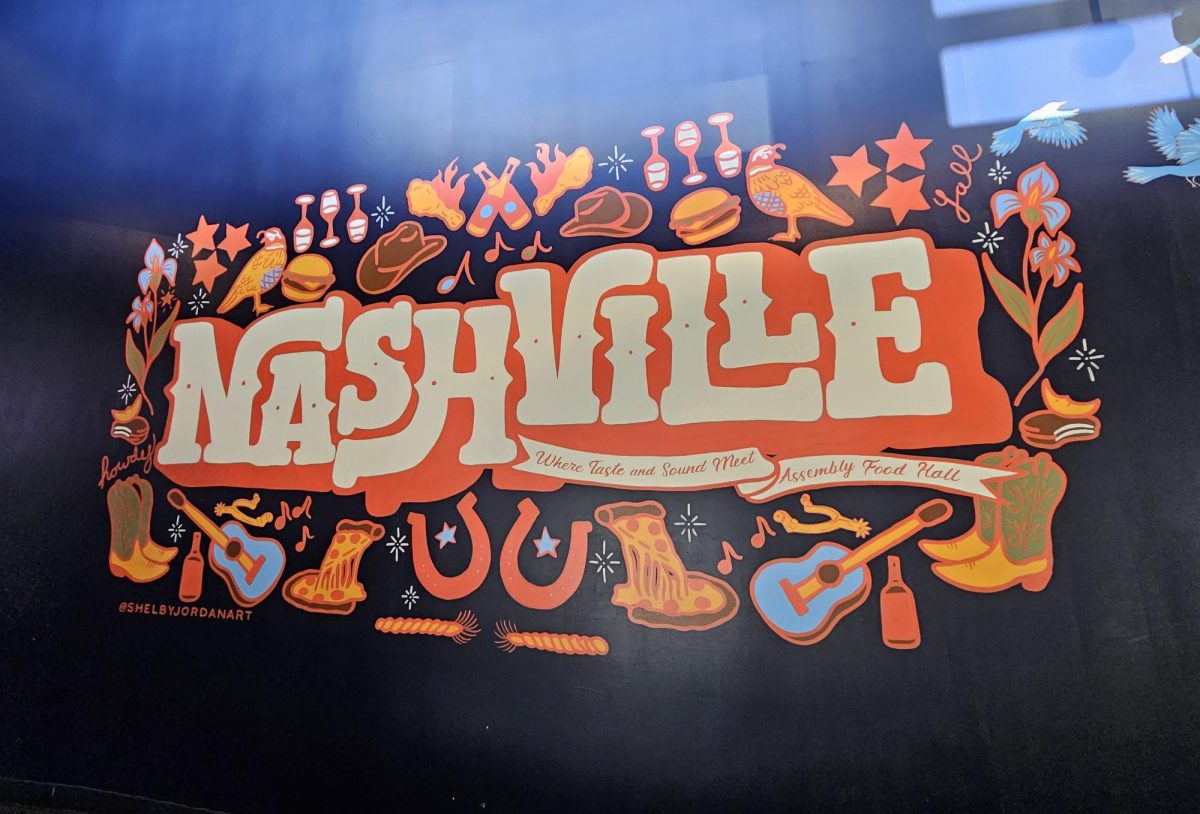

When I was younger, the mall was one of my favorite places to go to.

I loved how I could just spend my time there without an exact goal, simply existing there with my friends. When I went back last week, the food court was half-empty, stores were boarded up, and the few teens that were there didn’t seem like they wanted to be or that they were uninterested in what was there. It felt like the building had so much space, but somehow no real, welcoming space for them.

Something subtle but significant has shifted in teen life today. The familiar hangouts that once gave young people room to breathe, such as roller rinks, malls, and arcades, have quietly faded from the local scene.

That absence matters. What’s fading is something sociologists call the “third place,” a concept first introduced by Ray Oldenburg in his 1989 book The Great Good Place. According to the Albert Shanker Institute, a nonprofit organization established to honor the legacy of the late president of the American Federation of Teachers (AFT), third places are informal social settings that are not home, school, or work, but somewhere in between. These spaces can include cafés, parks, skateparks, after-school programs, and libraries.

For teenagers, these third places are not just casual spots to hangout, they are crucial for independence and identity formation. In such community-centered settings, teens learn who they are outside the constant supervision of parents and teachers. Third places contribute to social and behavioral development, offering an environment where youth learn many life skills, such as cooperation and self-management.

But now, the way teens interact with their communities is changing. According to Honor Society, an academic and professional society dedicated to recognizing high achievers, the decline of third spaces has accelerated in recent years. In their absence, kids gather wherever they can: parking lots, fast-food counters, and any corner of public space that will not push them out, they wrote. Adults scold kids about this, however no alternatives are offered by them, they added. We often forget that for teenagers, having somewhere to simply exist other than school and home is not a luxury–it’s a need.

Several factors contribute to this decline: commercialization, safety concerns, and the rise of technology, making this a larger societal issue, the society wrote. Meanwhile, technology offers a convenient but hollow substitute: virtual connection instead of physical presence.

But teen life has not changed only because their third spaces disappeared. Many teens do have access to new types of youth-oriented spaces, such as gaming lounges and structured after-school programs that provide teens with connection in their own way. Some teens prefer this kind of environment.

A study conducted by ScienceDirect, a platform designed to share scientific, health, and technical literature, said that when 540 parents of teenagers were asked to fill out a questionnaire, 369 out of those 540 parents indicated that their children do have a third place. At first glance, this seems to contradict the idea that third spaces are disappearing. But the key isn’t whether a teen has a third place or not, it’s whether that place meets all their developmental needs.

A teen who uses a school club as a “third place” still might feel they have nowhere to go after it ends. A teen who meets friends in a gaming lounge might enjoy it, yet feel they lack a free and flexible space. In other words, third spaces still exist, but they do not exist in the ways teens actually need or in the numbers that communities once provided.

This matters for communities like Glenview. Any effort to create new youth gathering spaces has to fit within the town’s budget and priorities, but that shouldn’t stop us from pushing for change.

Glenview residents should actively voice their support for teen focused spaces, ask village leaders where these ideas fit into long-term planning, and encourage the inclusion of youth spaces in future projects. If we want better spaces for teens to simply exist, then we have to speak up and make it a community priority.

I believe that we should not just preserve, but also work to create more third places where teens feel welcome–skateparks, recreation centers, low-cost lounges.

Some communities have successfully repurposed underused public buildings, such as old park district rooms or rarely used school facilities. According to multiple municipal reports across the U.S., buildings that operate at less than 20-30 percent of weekly capacity often become candidates for shared-used or youth-oriented remodeling.

While libraries remain heavily used and central to community life, other public spaces, like outdated fieldhouses, old administrative buildings, or unused school wings, often sit empty for most of the week and could be transformed into a teen-friendly environment.

Whatever form these places take, must be accessible, safe, affordable, well-located, and loosely structured so that teens can exist on their own terms without any pressure. Additionally, teens should have a say in designing and programming these places so that they truly reflect what our generation wants and needs.

All in all, third places are greater than just nostalgia. Instead of just having somewhere to go, teenagers need somewhere to grow, and belong. Without these third-places, teens risk losing important senses of community and connection.