Finals weighting disproportionately affects semester grades

Illustration by Chaeyeon Park

February 9, 2018

Semester one was filled with 54 gold days and 54 blue days. This means senior Nicole Herdman* had 108 different opportunities to prove herself worthy of a particular grade in one of her more rigorous classes. On top of that, her estimated 10 hours of homework per week provided her with even more opportunities to construct her semester grade in this class.

Yet, at Glenbrook South, a student’s consistent effort throughout 54-108 sessions of an academic class, which equates to nearly 5,000-10,000 minutes, can be jeopardized and completely obliterated by one 90 minute test.

Herdman, who succumbed to the wrath of this final, watched her steady 82.5 percent semester grade drop to a 79.1 percent after taking her final exam. She expressed how Glenbrook South’s current system, which weighs final exams as 20 percent of a semester grade, is an inaccurate reflection of a student’s dedication toward a class and an inaccurate representation of their growth.

“On my test, [the final had] 130 questions in 90 minutes,” Herdman said. “It’s really hard to look at [complex information] and seriously analyze [it in that time]. I feel like [finals] are a test to how much I can memorize three days before finals instead of how much I actually know.”

Final exams across the country are designed and implemented into an academic school year to assess how well a student can cohesively entertain certain concepts. At Glenbrook South, these assessments, holding significant percentage weight, are part of a system I consider to be in vital need of improvement.

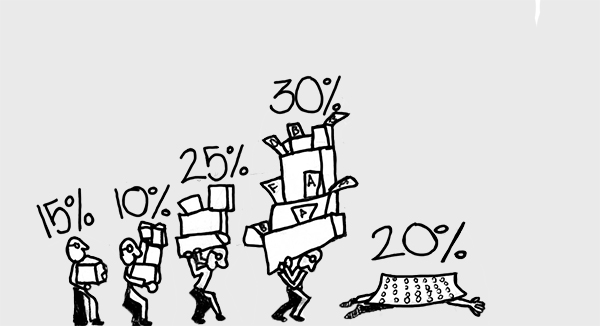

In a non-scientific Oracle conducted survey, 61 percent of 273 surveyed South students specified they have dropped a letter grade after not receiving the score on a final exam they needed to keep their semester grade.

My condolences go out to all 61 percent of those students who have needed to deal with the fact that their transcript will inaccurately articulate the evolution of their learning.

This statistic is one of the many problems with the current system in how final exams are administered here and how they are weighted. There needs to be change.

I believe this change should start with department discussions on how courses can capture a wider range of skills on final exams, on top of halving the weight of all final exams from 20 percent to 10 percent.

While there is speculation that the administration has been investigating the possibility of modifying the finals policy, the presence of them on a lower pedestal may be able to please supporters on both sides of the issue.

Benedict Hussman, social studies teacher, believes that while final exams do not necessarily need to be weighted 20 percent, the presence of them is still crucial to embedding key themes from course curriculums into the brains of students. According to Hussman, taking final exams as high schoolers gives us the opportunity to prepare for final exams in college.

“I think we have to recognize that most Glenbrook South students are college bound; they’re going to be going to college courses where there may be one or two tests and that’s it,” Hussman explained. “That’s your grade. And so these [finals] have really big weights. And if students haven’t been through something where it counts a lot, I fear that that will be a nasty experience in college that they don’t realize.”

Final exams personify the realities of college which many of us will inevitably need to face when we encounter these grueling tests. However, lowering the ‘final exam’ category in the gradebook to 10 percent will remedy not only the chaotic effect final exams have on our routine during the two weeks after break, but it will also allow students to still obtain an accurate reflection of their progress in the course even if the final exam doesn’t cater to their set of skills.

According to English teacher John Allen, while the concept of final exams holds important wisdom, the task of evaluating a student’s integration of concepts can be accomplished through giving comprehensive low/medium stakes evaluations throughout a semester. Allen explains how looking at a student’s semester progression from a holistic view can paint a strong picture of their growth in the course.

“What I’ve observed is everybody has a basket full of skills with different skills at different levels, so there are kids who are excellent speakers, not so good writers, [and vice versa],” Allen said. “[The students] have a basket of activities, [teachers] judge the basket as a whole, and you get this much more valid picture of who this kid really was during the learning segment of the course.”

The disruptive element caused by final exams, which steals two weeks of learning opportunities out of a semester to focus on these high-stakes tests, can be easily tamed by lowering the percentage of finals. Counting finals for 10 percent will cause less emphasis toward the tests, therefore less need for teachers to spend the week after winter break scrambling to review during class. With this change, students would still be exposed to the demanding hours which studying for a final exam entails.

Despite the side you take on the issue, I think we can all agree at the end of the day, our experience here at South is primarily about the learning. Let’s stop allowing one test to upstage a semester’s product of hard work.

And to all the grades we once earned but lost in the process of final exams, may you and your hardwork rest in peace.

* Name has been changed