Speech opportunities must be consistent for all students

Students at a disadvantage for future without adequate public-speaking practice

December 22, 2017

It’s no secret technology plays a bigger part in people’s lives than ever, and there is little doubt the trend will continue. However, as people move to digital communication, the importance of face-to-face interactions and public speaking remains prevalent as ever. Yet, some South students lack the necessary experience to hone this skill.

With the 2015-16 elimination of the Communications, a class designed to teach public-speaking skills to students, coupled with a lack of consistency among classes for presentation opportunities, the Oracle Editorial Board urges the South English Department to create a minimum amount of speeches and presentations per class, which according to the English Department’s Team Leaders is not currently in place or remains at a single speech per semester.

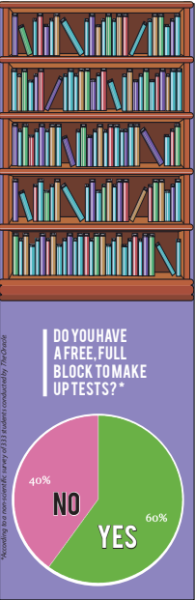

As it stands, GBS students receive unbalanced exposure to public speaking. In a nonscientific Oracle-conducted survey of 329 students, 21.3 percent said they had an average of zero public speaking assessments for their English classes over the course of a typical semester. Furthermore, 34.3 percent said they had an average of one speech and 24.9 percent had two.

All South students should be given equal tools to improve upon their public speaking and equal opportunities to showcase them. Allotting a certain number per semester, that number being up to the English Department’s discretion, would remedy the imbalance while maintaining a routine of practicing for public speaking.

The routine of public speaking was an integral part of Communications, ensuring that students stayed in the habit of giving speeches. Beth Ann Barber, former Communications teacher, says she advocates for a distinct communications curriculum because, with frequent speeches, students avoid the apprehension that may result from long periods without public speaking tasks.

“With Communications, I could see those kids who really hated it and were scared; I could watch the growth,” Barber said. “And I could still see it, certainly, in the English class, but not to the same extent. You could see [students] improve in confidence and really grow, but in [these current classes] they might do one or two speeches and then it’s not for another two quarters before you’re doing the next major public-speaking situation.”

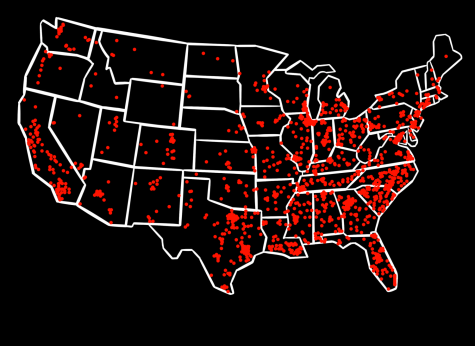

Practicing consistent communication in classrooms would also help ease some students’ fears on public speaking. The hesitation is common: a 2014 Chapman University Survey on American Fears says 25.3 percent of Americans fear talking in front of crowds, making public-speaking the nation’s most widespread phobia. In an academic setting, however, students would be able to practice in front of peers and teachers.

With repetition, and barring social anxieties that make the task physically taxing, students can learn to be comfortable presenting their ideas. Additionally, teachers are uniquely suited to advise students and help them improve.

Although this generation is marked by the unique opportunity to interact with others through the Internet, presentation skills remain vital to success post-graduation. Seventy percent of employed professionals whose jobs include public-speaking consider it “critical to their work,” according to a survey conducted by Prezi, an online presentation platform. Developing public speaking takes time and practice. To not foster this process throughout high school makes South students more ill-equipped in future endeavors.

Debbie Cohen, Glenbrook North English teacher, worked at South as Freshman Team Leader when administration decided to remove Communications from the freshman curriculum. Tasked with implementing that choice, Cohen says the challenge of fitting introductory reading, annotating and research skills along with presentation experience resulted in the hardship of having speaking opportunities dispersed over longer periods of time.

“Just like anything else, we expect reading and writing to be instructed at every grade level and speaking and listening skills should be as well,” Cohen said. “So, my thought about how that could be improved is a bit more explicit instruction to speaking and listening standards across grade levels as opposed to simply expecting one semester—whether it’s a one semester course or an integrated year-long approach. I don’t know that either of those approaches will work if we only treat speaking and listening as something that’s important for freshman to learn and never have that explicit attention again.”

With technology’s expanding role in our everyday lives, many students are losing precious skills necessary to our success in both professional and personal life. With the removal of Communications and its integration into the English sequence, South runs the risk of students missing out on optimal opportunities to practice public speaking without a minimum.