Diversified friendships broaden understanding, perspective

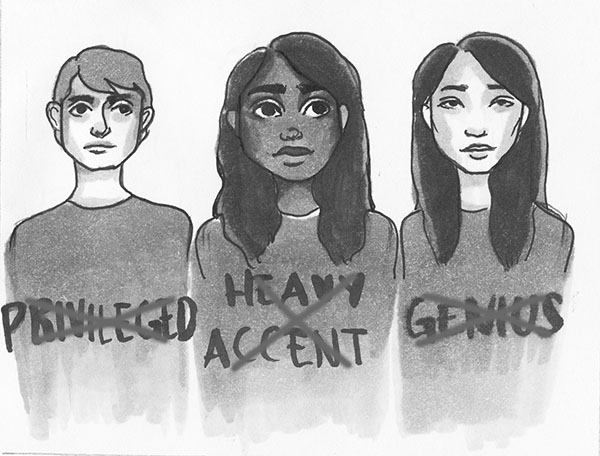

Illustration by Sarah Warner

December 16, 2016

As I crossed Japanese customs in the summer of 2013 on my way to visit my best friend, Mio, I immediately entered my own version of Where’s Waldo? Except, instead of readers scrambling for hours to find me, I was a black dot on a completely pale white page. I mean with 99.4 percent of Japan’s population being either Japanese, Korean or Chinese, and a minuscule .06 percent labeled as ALL others, Japan’s demographic was stacked against me, and I was clearly visible.

Yet surprisingly, instead of harassment, Japanese natives greeted me with curiosity. Questions they asked spanned from “What’s America like?” to “Are you related to Michael Jackson?” I happily assured them that the American Dream is attainable, but shattered hopes when I broke the news that despite my last name, I’m not, in fact, related to the King of Pop.

Although they gained facts about America from me, I gained insight from them. Lacking diversity, Japanese natives are deprived of experience with people of opposing viewpoints and unique backgrounds, teaching me to value America’s diversity. Although Glenbrook South’s race ratio doesn’t resemble our whole nation’s, I firmly believe we should take advantage of the smidge of diversity our school has to offer. Surrounding ourselves with people different from us ends cultural and racial ignorance and makes us well-rounded human beings.

Growing up in New York, the world’s melting pot, I came across every shade imaginable: pale, ivory, light brown, olive, dark and all skin tones in between. New York’s diversity, along with my parents, taught me that skin color isn’t important, while my mixed friend group taught me that race doesn’t determine relatability. Yet, a simple move made me turn from a girl that didn’t care about race to one that obsessed over it.

When I was 11, my life was picked up and plopped down into suburban Glenview like a claw arcade game, and things changed. Seeing Glenview’s small-scale diversity, initially, I had a strong urge to latch onto other black students for comfort. I vividly remember walking my Attea schedule for the first time and mentally making a deal with God, naively and innocently pleading, “If you put at least one black person in each of my classes, I will repay you.”

This internal struggle to stay with your race isn’t unique to me. It’s an unsaid idea that transcends all racial lines, advanced by social media, close-minded family and culture. Even six years after moving to Glenview, I still haven’t completely shaken the idea. Whenever I cross paths with the black clique, an unexplainable and uncontrollable guilt wells up. I think to myself, “I should be with them.” But I quickly shove this thought down.

I shove it down because I’m reminded of my distant relatives. Hailing from Detroit, Michigan, my family didn’t get a lot of experience with different races creating a one color world-view, and whenever I visit them, I feel like I travel back in time. Like many others, they’ve created stereotypical boxes for each race. East Asians must be geniuses, Caucasians must be privileged, South Asians must have heavy accents, so on and so forth. But what happens if you don’t fit in “your” box?

Well, you’re put smack into another one. For example, being defined as “whitewashed.” I’ve been called “whitewashed” and have friends who call themselves “whitewashed.” When we don’t fit a pre-made template, we find other ways to define ourselves.

When an Asian doesn’t know their native language or an Indian isn’t in Bhangra Beats, they are defined, and oftentimes define themselves, as “whitewashed.” This word carries a negative connotation, signifying that you’ve lost part of your identity. But each person is a unique individual, not a product of their race. Branching out deletes these racial boxes and the pressure to fit inside them.

Not only that, but interacting with people of contrasting cultural backgrounds has broadened my knowledge. I’ve learned about small things like the Asian double eyelid surgery obsession to different cultures’ cuisines. The biggest influence diversity has had on my life is creating a love and curiosity for exploring cultures. I’ve been studying Japanese for three years since visiting Japan in 2013 to see my best friend, Mio. If it weren’t for Mio, Japanese wouldn’t be a part of my life.

Scanning my close friend group, I see an ambitious Mexican obsessed with linguistics, a hilarious Muslim Malaysian pursuing art, a die-hard Christian Japanese girl and a history geek Catholic Polish girl. Surrounded by contrasting cultures, unique personalities and a scale of struggles, I can’t help but internally smile.