I’ve learned a lot over the course of my 12 years in the Glenview schools. I learned how to read, for example. I learned how to draw a unit circle and compare myself to others and all sorts of stuff. I also learned that nothing is more valuable than my ability to answer aloud any question a teacher might throw at me.

Most classes I’ve taken, both at South and in middle school, have had participation grades. Designed to create an animated classroom where everyone contributes to conversations equally, they can easily become a major source of unnecessary stress for the kids who just aren’t made to talk that much.

Believe me, I’ve tried to fit the mold. Second semester freshman year I made it my mission to get an A in participation in every class. It didn’t last long; by the time I finished painstakingly transforming my thoughts into words I could say out loud, the class had moved on.

Then there were those few kids whose willingness to answer every question regardless of whether they actually had an answer pushed me even further toward the sidelines. I left the few classes I actually managed to talk in exhausted and resentful. I just couldn’t do it, and a constant nagging D on my Powerschool didn’t change that.

Participation grades also have a tendency to make kids so focused on getting their points that they don’t really listen to or connect with anyone else’s comments.

Just take a look at any classroom graded discussion. Few students actually respond to each other. The discussion just ends up with people taking turns making comments they planned the night before.

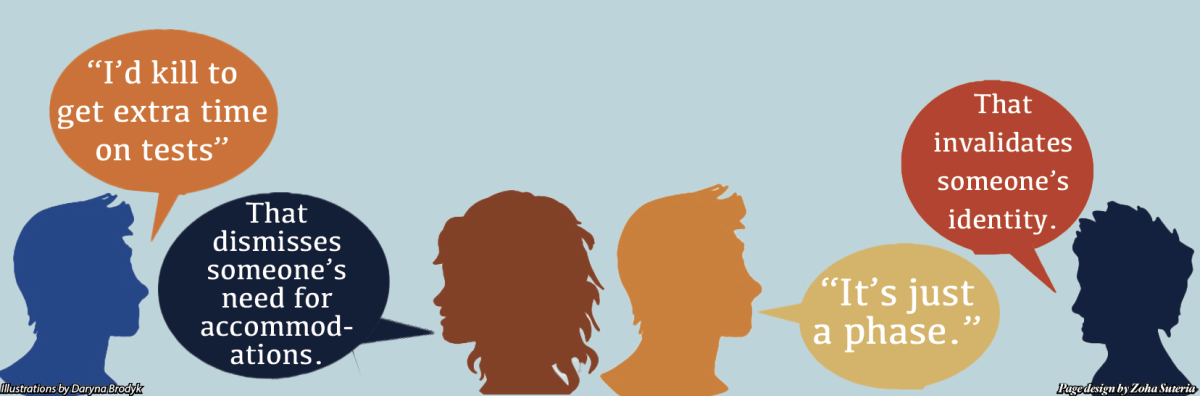

I understand the perceived necessity of participation grades; a lot of kids talking means more engaged class discussions, which should make things better for everyone. Verbal responses to questions are an easy way for teachers to ensure students are engaged, and the ability to ask questions and express opinions verbally are highly valued in an extroversion-rewarding American culture. It’s a necessary skill.

None of this changes the fact that people learn and respond to information in different ways. For some kids, that’s talking about it. That’s the way that we as a culture tend to prefer, and it’s totally 100 percent okay. But some of us just don’t do that, and that’s just as valid.

If the issue is engagement, giving students the last five minutes of class to write down their thoughts on the day’s material is one way to ensure everyone has a chance to share their thoughts. What they write could be taken into account along with their verbal participation. If it’s a question of understanding, talk to them one-on-one.

Even if nothing in the grading system actually changes, it’s important that teachers take a step back and consider why some kids aren’t “participating” before immediately labeling them as unengaged. We exist, we’re engaged, and we’re tired of being penalized for our natural tendencies.