“Je suis Charlie.” I am Charlie. This slogan has become the most recent battle cry of proponents of free speech and expression in the wake of the Jan. 7 attacks on Charlie Hebdo, the French satirical magazine.

The slogan is meant to bring unity in a world so seemingly lost in chaos and violence. In this case, it is meant to oppose the violence of the Paris terrorist attacks. These are three simple words that convey so much more, from feelings of empathy, to support for the victims, to a condemnation of terrorism and a defense of our perceived freedoms.

Twelve journalists, including the editor of Charlie Hebdo, were murdered by radical Islamists offended by the depictions of Muhammad in the magazine. While receiving the sympathies of the world, this incident has also rekindled the debate over the freedom of expression.

It is important to understand that Islam prohibits images of its prophets, including Muhammad. Thus, the magazine’s critical portrayal was even more inflammatory. However, I don’t think people should ever have to restrict themselves from speaking their minds for fear of violent repercussions.

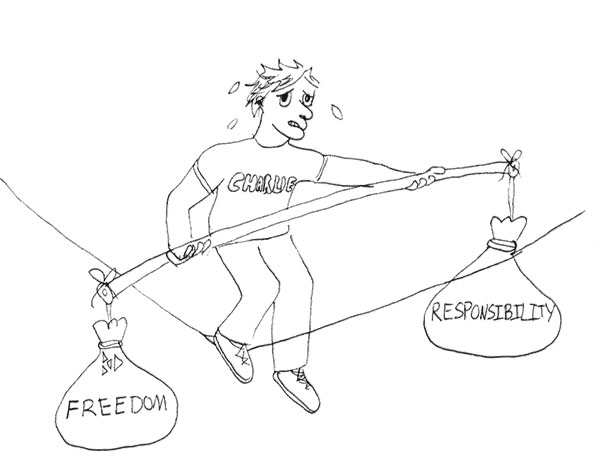

As someone who would like to think of himself as a journalist, and someone who likes to speak his mind in general, I value our freedom of speech, press and expression that we are granted in America. However, this is not to say that this whole experience has not been confusing and difficult for me.

In looking at the bigger picture, we should realize that freedom of speech is rarely absolute. Even in the United States there are limitations to everything and anything you want to say. France’s speech-restrictive policies in fact go farther than those in the United States.

Under French law citizens cannot insult, defame or discriminate against a person or group of people based on their ethnicity or determined religion. However, they are free to challenge and criticize ideas, practices or symbols of religion. This means you can hate the practice but not the person.

This line between freedom of speech and something that goes too far is one that Charlie Hebdo has tip-toed exceedingly well for years. The magazine has been sued by Muslim and Catholic groups for various depictions and caricatures of Muhammad and the Pope in the past. In all these instances there was only one in which the magazine did not win the lawsuit.

Now we know that, legally speaking, the actions of Charlie Hebdo were and are defensible. I now wonder whether there is a question of morality that should be introduced into the debate over free speech.

We shouldn’t make martyrs out of provocateurs. But, Charlie Hebdo was not trying to hurt or actively provoke any individual. Their remarks and caricatures were all made against larger institutions.

Satire is and always will be a rather difficult form of expression to understand. But the answer isn’t to say less, it is to say it better. Finding the right words to a situation is hard, but if this “Je suis Charlie” movement proves anything, it proves that the words can be found.