Pen in hand, textbook open and music playing, I set out to finish my daily homework assignments. The melodic arpeggios rose and fell in succession, compiling into lyrical refrains both familiar and foreign to me. As the music continued to play, I contemplated whether listening to music while I work was helping me focus or acting as a distraction.

The short-term positive improvement of psychological activity while listening to the classical pieces of Mozart, otherwise known as the “Mozart Effect,” is a widely controversial topic among psychologists. Some people believe that it is distracting to listen to music in general, whereas others believe that listening to certain genres of music, especially classical, can improve productivity.

In 1988 at the University of California at Irvine, neurobiologist Gordon Shaw, with the assistance of graduate student Xiaodan Leng, conducted a study on brain activity. He found that brain activity, when put through a computer and the waves are played audibly, can simulate sounds similar to that of baroque music, or classical music.

Joined by researchers Frances Rauscher and Katherine Ky, Shaw furthered his research by conducting his experiment in reverse: studying the brain’s activity in response to classical pieces composed by Mozart, eventually coining the term, “Mozart Effect.”

In his study, Shaw and his fellow researchers were able to produce subtle yet existent evidence that Mozart’s music does affect the brain. In spite of this, further studies conducted at other universities, including the State University of New York at Albany and the University of Auckland, failed to produce evidence suggesting that Mozart’s music can improve brain activity.

With these two contrasting conclusions in mind, I decided to put the Mozart Effect to the test. Over the course of six days, Sunday through Friday, I put on three different types of background sound. For two days, I listened to classical music, specifically by Mozart; another two days were spent listening to alternative rock, a genre I particularly enjoy; on the final two days, no music was played at all.

Throughout the six days, I kept a relatively consistent amount of work, increasing or decreasing the workload as needed by pushing assignments off or doing others in advance. Abandoning the proper methods of measuring brain activity, I merely counted the hours in which I was productive, thus comparing the hours to see the times in which I was most productive.

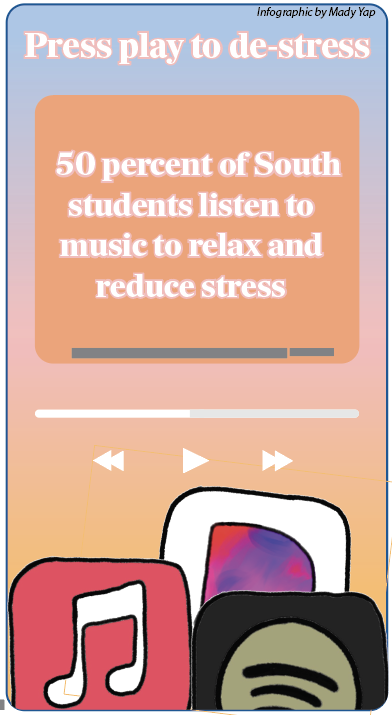

After the six days were complete, I found that the hours of productivity in which I listened to music, both classical and alternative rock, were relatively more than the days that I spent listening to no music at all. Contrary to the belief that music acts as a distraction, I felt content and able to finish the work at hand with music playing in the background.

When listening to classical music, my brain felt stimulated, just as Shaw’s experiment described, to the point that I could complete work with a minimal amount of difficulty. As for the genre I preferred, it seemed to have the same effect to a slightly lesser extent, serving as a way to relax my brain and enable it to perform the tasks at hand.

This result led me to believe that music does create some mental stimulation. In my experience, classical music stimulates the brain more than music with lyrics, simply because there is less of a tendency to stop what you’re doing and sing along. But, as a whole, music improves productivity over silence to keep the mind moving.

All in all, I do believe that the “Mozart Effect” does exist, but not to the extent as to make you a genius overnight. If you are planning on studying for a test or completing a long essay, I would recommend listening to Mozart or even your preferable genre of music in order to drown out the background noise of everyday life. As the wise Martin Luther King once said, “Beautiful music is the art of the prophets that can calm the agitations of the soul,” words that I hold true after experiencing the benefits that music has in store.