Why the hell do we go to college?

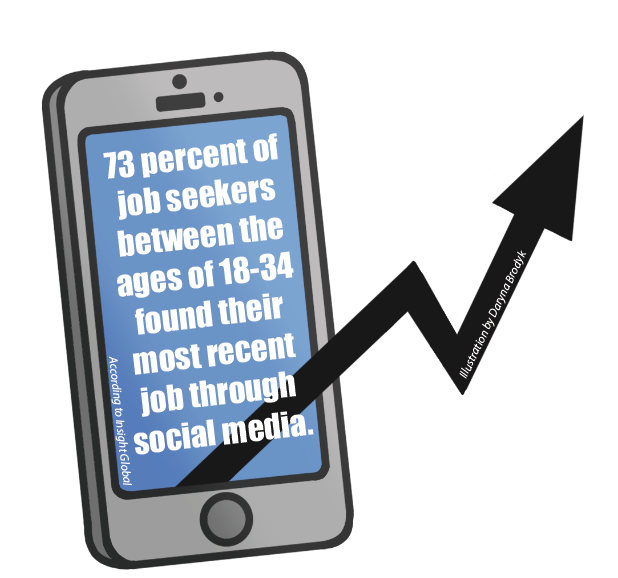

Of course there is always the noble (and mildly dishonest) minority that say the purpose of higher learning institutions is to gain an education that will enrich our lives. But the majority of us would most likely agree on the actual reason: people go to college so they can get a job.

The process has been essentially the same since the ‘50s. Jimmy works hard in school so he can get into a good college; Jimmy works hard in college so that he can make a good career for himself; Jimmy works hard in his career so that he can send Jimmy Jr. to college. Lather. Rinse. Repeat.

That is until late 2007, when the nation entered what became sardonically known as the “Great Recession.”

You know the story: several of the nation’s most affluent industries suddenly found themselves in dire circumstances, foreclosures became water cooler talk. Needless to say, a new suit and an Ivy League Bachelor of Arts fresh-off-the-press isn’t the golden ticket it used to be.

According to the Chicago Tribune, between September 2010 and January 2011 about 1.94 million graduates under age 30 were “mal-employed”—a term coined in the ‘70s for graduates who had to serve in low-skill jobs because they could not find ones that required a degree.

Of course this statistic is deeply unsettling for a soon-to-be college-bound student such as myself. However, I can accept that these conditions are out of any average human’s realistic control.

What’s more troubling to me is the utter failure by the US’s colleges and universities to adjust to these conditions. In fact, their actions are deepening the wound.

Allow me for a moment to take all romantic notions out of institutions of higher learning: colleges, like many other institutions in this world, are a service. They’re meant to educate the youth and provide them with a greater ability to secure a career.

Among those who agree with me is a recent graduated class of law students from New York Law School (NYLS). Now NYLS made a key error here: they ticked off a bunch of freshly educated law students with too much free time. So what did the students do? File a $200 million class action suit against the school, of course.

The students claimed that the school grossly misrepresented and inflated post-graduate opportunities for lawyers, while also burgeoning them with colossal debts, equating the situation to what they called “years of indentured servitude.”

The students also claim NYLS’s Dean Richard Mastasar acknowledged this very problem when he said, “If [the students] don’t have a good outcome in life, we’re exploiting them. It’s our responsibility to own the outcomes of our institutions. If they’re not doing well, […] it’s got to be fixed. Or we should shut the damn place down.”

Law students across the country are following suit (no pun intended) with similar law cases taking place in Chicago, Detroit, California and other places. These students see what I see—it is the responsibility of these kinds of institutions to provide students with resources for their careers after graduation.

Yet in an economy where these careers are becoming harder to secure, rather than adjusting their costs or tools to aid the students, college and university tuitions are skyrocketing.

Yes, college is supposed to provide a person with more than just a career, and I’m not claiming that colleges are responsible for a graduate’s unemployment. Additionally, some institutions of higher learning do in fact tweak their curriculum to meet the needs of the job market, but not overwhelmingly so. By lowering tuition (or at least keeping it constant), or by directing students to industries where more jobs are open, colleges and universities would no longer be exasperating a problem that is their job to relieve.