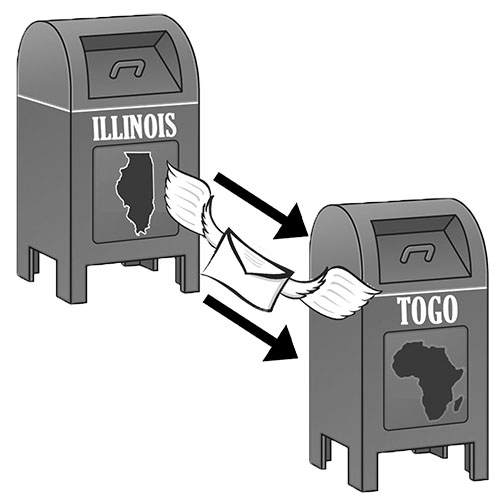

French classes extend reach to Togo, broaden geographic outreach

Graphic by Jacqueline DeWitt

March 11, 2016

Halfway across the world in remote West Africa, Togolese students are receiving the work of South students. French classes, led by Matthew Bertke and Catherine Klahn, recently created projects and wrote letters which were sent to students in Togo.

The West African country of Togo is a French-speaking nation. According to Bertke, focusing on this region provides a way for his students to expand their knowledge and skills of the French language.

“I studied abroad in Burkina Faso which is just to the north of Togo,” Bertke said. “I know that there are tons of Peace Corps volunteers in West Africa, and so I wanted my students to get to know the West African French-speaking world. I [also] wanted to give my students an audience for their French by using their French outside of the classroom for a purpose.”

The project started when Bertke was on the Peace Corps website and came across the opportunity to connect with Brian Palmer, a Peace Corps Volunteer stationed in Togo. After an email exchange, Palmer suggested creating brochures on American national parks since he had just opened an environmental club at a Togolese school he helps at, according to sophomore Michelle Barsukov.

“The Togolese people already know their own geography but this would be a way to teach them about the geography of the U.S. and also because they speak French, we would write these brochures in French,” Barsukov said.

Some French classes taught by Bertke and Klahn have created brochures talking about the differences between national parks in the United States and ecological zones in West Africa. Sophomore Kayt Ribordy, an Honors French Three student who participated in the project, explained that the brochures were created to send to the Togolese students. Each brochure covered one national park and discussed different aspects of the park.

“Our group got the Rocky Mountain National Park,” Ribordy said. “We had six different sections and they each had a different topic. For mine, I did the plants that were found there, someone else did animals […] and someone else did climate and geography.”

After the brochures were completed, students presented their findings to the class. According to Barsukov, the presentations were designed to compare North American geography with that of West Africa.

“My group did the Yellowstone National Park, and so we presented [to the class] on the Great Rift Valley, which has geysers and hot springs and things like that,” Barsukov said.

According to Barsukov, the presentations broke stereotypes about the continent of Africa as a whole.

“It kind of put the world into perspective to show [that] we are not quite as unique as we think we are,” Barsukov said. “In a way that’s good because we can connect with people that we never thought we’d be able to [connect with].”

Bertke echoes Barsukov’s statement about stereotypes, and feels that ending of some of these stereotypes has been his greatest takeaway from the project.

“With the brochures, [I liked] watching my students have a conversation about stereotypes that were broken without any real direct instruction. All of these stereotypes [of Africa were] formed based on what the media gives us. [Changing] our thinking about [Africa] was the most interesting thing for me.”

Bertke also explains that breaking those stereotypes has a big impact on uniting the global community and increasing student exposure to the world.

“We are all human beings and we all live in this planet,” Bertke said. “We all have big stereotypes about what we believe a small community in West Africa might look like. I can only go so far as a teacher in front of the classroom. To give them real-life examples that will break the stereotypes of elephants running everywhere, poverty and no education will give them a bigger global picture [of West Africa].”

According to Bertke, there is a big difference in infrastructure and development between West Africa and the United States. Due to the fact that West Africa is less developed than the U.S., Bertke predicts it will be a lengthy process to deliver, read and respond to letters. He feels this has the possibility to inhibit the communication process between the students.

“Glenbrook South [runs] much faster,” Bertke said. “We are a high pressure, high performing school. Most small towns in West Africa run with a much slower pace of life, which is something I found to be true when I lived there.”

According to Ribordy, the project has a purpose, because both students at South and students in Togo are benefitting from it. While the project is breaking stereotypes for students at South, at the same time it is also increasing Northern American geographical exposure for the students in Togo.

“It’s a useful project,” Ribordy said. “These brochures weren’t going to sit in the back of a teacher’s desk somewhere. They were going to Togo […] to help these kids learn about different geography in North America. It felt like we were actually making a difference.”