To read this article means it has not been censored. However, the opinion of whether censorship should or should not be an option varies for South’s students. To some South students, censorship is a violation of their first amendment rights, yet others feel that censorship is protecting teens from inappropriate and harmful material.

According to Dictionary.com, censorship is “the practice of officially examining books, movies, etc., and suppressing unacceptable parts”. From an unscientific Oracle-conducted survey of 171 students, 88 percent believe there is no circumstance when censorship should be allowed. For sophomore Charlie Smith, limiting or changing content taints the true meaning of the author’s original point.

“I believe that [censorship is] not okay because in a lot of cases, the material in question is part of the artist’s vision of what the book […] would be, and if you mess with that, you’re messing with the […] artistic intent,” Smith said.

Having similar views as Smith, Susan Levine-Kelley, instructional supervisor (IS) of the English Department, works with all English teachers in deciding if a book is appropriate for the curriculum. According to Levine-Kelley, although the District 225 board must approve all books before they are added to the curriculum, the English department has built lasting trust with the board. Therefore, they have never encountered a censorship disagreement in Levine-Kelley’s 10 years at South.

“We are, I think, among the luckiest districts […] in the sense that our […] board has so much trust in the texts that we choose,” Levine-Kelley said. “And it’s not that they don’t ask questions; they ask great questions and they ensure that we are choosing texts that support the kids learning and that are important to the curriculum itself.”

Although the English Department has never experienced censorship in Levine-Kelley’s years as IS, she does acknowledge that it can occur in the future. Though she highly doubts this will happen, Levine-Kelley believes the English Department must respect the board’s wishes if a case of censorship occurs.

“If […] [a] principal said, ‘No, you can not use this book,’ it would not be good for morale,” Levine-Kelley said. “[…] But if it did happen, we would have to [censor], of course. We can’t be insubordinate in that way. […] We’d have to go back and choose another book because [the board is our] safety net […] intellectually, emotionally, and legally. So if the board members couldn’t support something, then we have to respect that.”

As Oracle Advisor Marshall Harris works side-by-side with journalists, the rules and regulations of freedom of the press apply to his everyday work. Despite his strong personal opinions in favor of the first amendment, Harris recognizes the fine line between inappropriate language and themes. According to Harris, although he tries to leave the ultimate decision to the editors, certain circumstances, such as during column writing, which is different from standard journalistic writing due to the writer’s freedom to express their opinion in the writing, can make him question that decision.

“I think [inappropriate language] becomes potentially a distraction,” Harris said. “I know that for a certain segment of the audience, that will become the entire focus of […] the column, and the overall outstanding point […] will get lost.”

Harris described what actions he would take if the writer did not take his advice on replacing the inappropriate language.

“I would have [a] conversation with the columnist and with the opinions editor, and I think that ultimately [the editor and the writer] would make the choice. If they refused [my suggestions], would I “censor” it? It’s never come to that, but if it did, I honestly don’t know.”

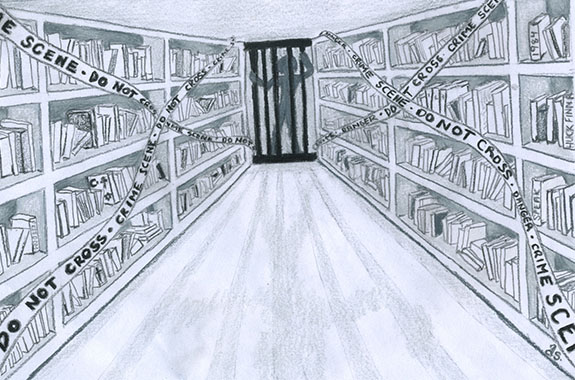

South’s library also faces “fine” lines when determining if a certain book is too inappropriate for a high school audience. According to Librarian Kris Jacobson, although the library supports banned book week sponsored by the American Library Association (ALA), which encourages people to read and learn about banned books, they sometimes encounter certain scenarios when a book should be removed from South’s shelves, specifically concerning violence-oriented literature.

“The library’s view is that censorship is a bad thing, but having said that, I would be lying if I didn’t say we’ve engaged in […] selective policies that are de facto of censoring things because we’ll say, ‘Eh, this isn’t right for our audience,’” Jacobson said. “We wouldn’t buy it […], so I would be lying if I said that the goal of a school library is to give everyone any information they could possibly access.”

The fine lines are not only recognized by teachers but by students as well. Although sophomore Nurul Hana Mohammed-Rafee condemns strict censorship, she believes there should be fewer thematic discussions in order to accommodate all opinions. Additionally, Mohammed-Rafee feels that if a student is uncomfortable with a topic, they have a right to walk out of the class, but be encouraged to seek their own form of education on the particular lesson in the future.

“I believe that everyone should be able to talk freely about what they want, but if there are certain subjects in which students feel uncomfortable […], it should be discussed with the class,” Mohammed-Rafee said. “I believe [the people discussing the topic] should decide […] whether they want to stay more quiet […] or talk about it in a more respectful level. It’s not exactly censorship, but it’s more like just lowering the levels of how much you talk about a certain subject.”

For Mohammed-Rafee, censorship is affected by the presence of stereotypes in society and the variety of reactions and opinions associated with them. In her opinion, the way to lessen the controversy with censorship is to be open-minded towards all views and eliminate the use of stereotypes in general.

“[Teachers] should talk about everything, but just recall that some students just can’t handle some things […] especially when teachers start talking about current events like say talking about terrorism [in general],” Mohammed-Rafee said. “Someone brings up stereotypes about Muslims or Arabs […], then that starts to make some people uncomfortable. […] Instead of wondering what they should censor and what they shouldn’t censor […], they should learn how to maybe get rid of stereotypes and to just look at something from a [broader]view.”

With the fine lines of censorship in mind, Harris still appreciates his students’ ability to take advantage of their first amendment right with regards to the freedom of press.

“It feels really gratifying because to me, a real journalism education is not just about writing and design and editing; it’s about how to handle that right and responsibility of that freedom of speech,” Harris said. “And so my feeling about it is one of pride in what we are able to do.”

Harris also believes that the act of publishing sensitive content has reciprocal advantages for the school and the journalists who contribute to the publication.

“I would say that it serves a purpose for the larger school […] because if you couldn’t publish [stories about controversial topics], then conversations about those more controversial topics don’t take place,” Harris said. “So to me it has a great benefit for the kids who come through the journalism program, but also for the school community as a whole.”

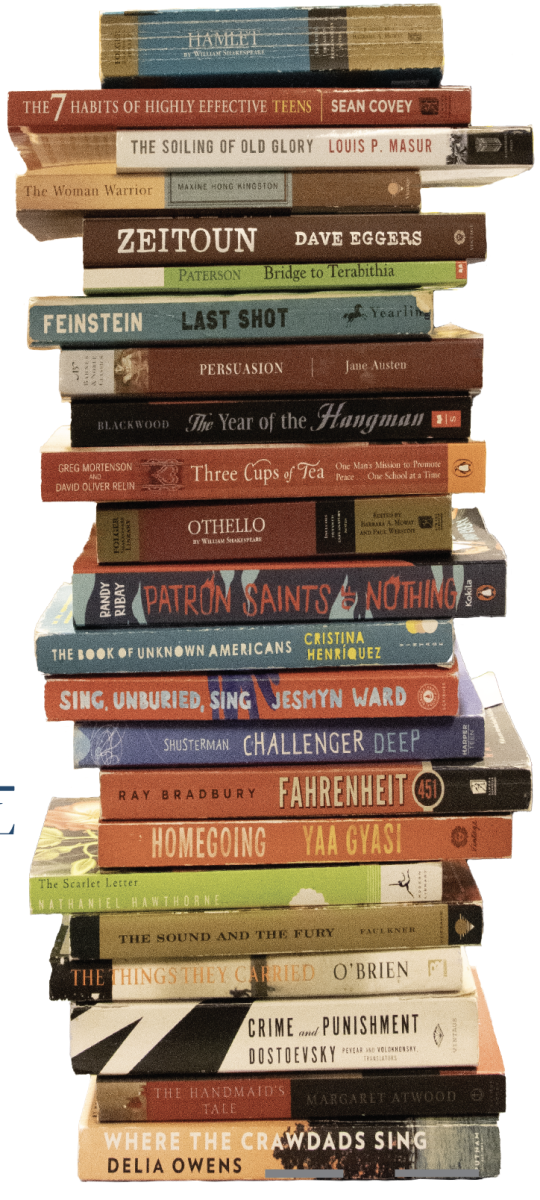

Levine-Kelly also wishes to contribute to student learning through controversial topics. Similar to Harris, the English Department prefers to offer literature with complex themes in order to foster student education in an appropriate setting. According to Levine-Kelley, books used at South are chosen for the type of literature they are, and if they happen to be banned elsewhere, it doesn’t change the choice.

“We are looking to make students kind of question themselves in the world a little bit,” Levine-Kelley said. “We attempt to give mirrors and windows […]. So, we try to choose literature that both reflects student experience in some way, and then windows to the world. So we’re working to challenge students and make them uncomfortable in a good way. […] So that [the students] are thinking and growing, but not so uncomfortable that it’s going to shut down learning.”