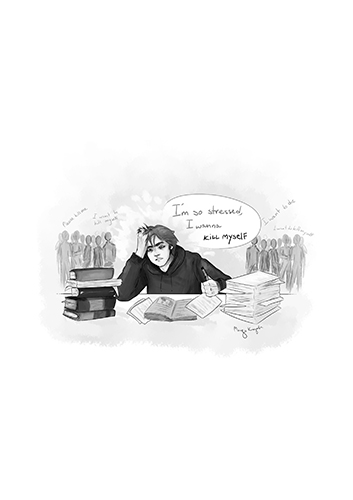

Suicide language becomes normalized among student body

December 14, 2018

While walking down the hall on the first day of school, I unlocked my phone to double check the room number of my next class. After a few moments of intently gazing down at my screen, my attention diverted to a nearby conversation between a junior boy and girl.

“I’ve had two classes and already have so much homework,” the boy nonchalantly explained. “I’m gonna kill myself.”

When I heard him, I froze. I could feel my face turn red, tears well up in my eyes, and clouded, painful memories flood into my head. I immediately looked down again at my phone wiped away the few tears, and headed into my next class astonished that the widespread use of suicide-related slang survived the summer.

You see, last year, I would have quietly smiled and laughed, hoping that they didn’t catch me eavesdropping on their conversation. Last year, I would have understood the response that jokes and exclamations like these always seem to garner. Last year, I would have gone on with my day without a second thought. Last year, though, I hadn’t yet lost someone I loved to suicide.

I’ll admit, it’s hard to know the consequences for saying things like this until your own experiences open you up to an entirely new world of understanding and emotional rawness, unreplicable by those personally unaffected by suicide. So, as one who has become infinitely more receptive of the pain and destruction phrases like this can cause, I’ll say this: suicidal speech and ideation is not “trendy”, and our societal attempt to normalize and integrate it into our everyday slang is both incredibly hurtful and, quite honestly embarrassing.

The transformation of saying “I’m gonna kill myself” to saying “kill yourself,” whether it’s a joke or not, should never be said by anyone, anywhere. You can never know who is struggling with what when they go home and shut their bedroom door. All it takes is one outside perspective to validate all of the negative, self-destructive thoughts and suicidal ideation that a person may have been internalizing and turn it into profoundly drastic, heartbreaking, yet avoidable action.

I love that we as a student body are not shying away from talking about suicide, but we’ve taken it down a path unintended by those who dedicated their lives to ending the stigmas. The idea is for everyone to understand and help those struggling fight their respective battles, not for us to pretend that we, too, combat these persistent and isolating thoughts on an everyday basis.

Suicide rates for those ages 15-24 have risen 1.9 percent from 2014 to 2016, according to the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention but we can contribute to reversing that by considering expressing the severity of our stress, embarrassment, or anger in another, more articulate way than “I’m gonna kill myself” or “I want to die,” and converting our apparent eagerness to talk about suicide into more productive conversations about national prevention.