The recent Syrian conflict has ignited a lot of controversy. This debate has largely focused on the legitimacy and wisdom of intervening in the conflict based on the Syrian government’s use of chemical weapons.

Chemical weapons, however, should not be the basis for military interventions – the distinction between such weapons and conventional forces is blurry and arbitrary.

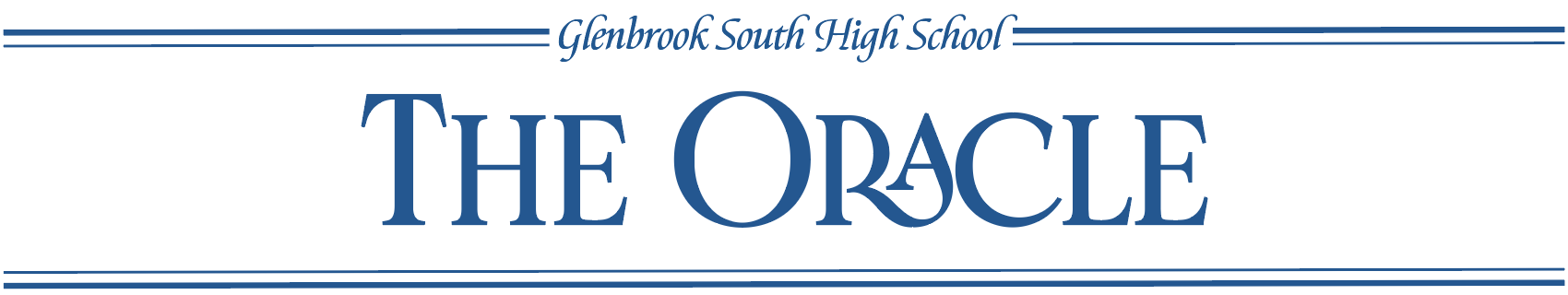

But first, a little background. In the midst of the Arab Spring uprisings of early 2011, the people of Syria followed the lead of Tunisia, Egypt, Libya, Bahrain and others to protest their oppressive government. In April 2011, the Syrian military was deployed to quell the uprisings, but the war spread nationwide and has been steadily growing more violent since then.

The UN estimates that the death toll reached 100,000 this past June, and tens of thousands of protesters have reportedly been imprisoned.

The recent controversy was triggered this spring when rumors abounded that Syrian president Bashar al-Assad’s administration was in possession of or had used chemical weapons, which led President Barack Obama to declare a “red line” over the use of chemical weapons – meaning the U.S. would have to intervene.

But why does the use of chemical weapons change the reality of the battlefield or the reasons for trying to stop the conflict? The distinction between chemical and conventional weapons in the context of the Syria crisis is, at best, arbitrary and, at worst, counterproductive.

The Economist also reported that around 1,500 people were killed in the worst chemical weapons attack this August. That’s (let me get out my calculator) 1.5 percent of the people that have been killed in the entire war – the vast majority of whom were killed with conventional weapons.

The uproar over the use of chemical weapons is just a way to justify a weak intervention way too late in the game and to save face with the war hawks who have been pushing intervention from the beginning. David Rieff of The New Republic described how the proposed strikes were too small to actually change conditions on the ground, but they were large enough to mollify warmongers and small enough to keep most of the activists quiet.

This is especially true when the kind of strike Obama proposed would have been counterproductive.

According to Ezra Klein of the Washington Post, a limited strike would at best take out Assad’s chemical weapons but also intensify his campaign against civilians with conventional weapons in retaliation. Statistically, according to Klein, leaders subject to international intervention in civil wars respond with more severe attacks against civilians in order to regain control over the conflict.

The common argument is that chemical weapons are indiscriminate civilian-killers, so they justify a harsher response. But let’s be real here – thousands of civilians have already been killed, wounded, or displaced. The method with which that is done is irrelevant.

Just several weeks ago, the U.S. and Russia reached a deal whereby the Syrian government would turn over their chemical weapons to Russian control, and the U.S. would effectively take military force off the table.

Even though a strike is not imminent, it’s important to understand the implications of chemical weapon use for the U.S. and the international community.

The U.S. should have either committed itself to full-on regime change and actually changed the conditions on the ground or simply have stayed out. Either way, the nation at large needs to reconsider its approach to chemical weapons. They should not be the basis for weak, politically motivated interventions that distract from the real conditions on the ground.