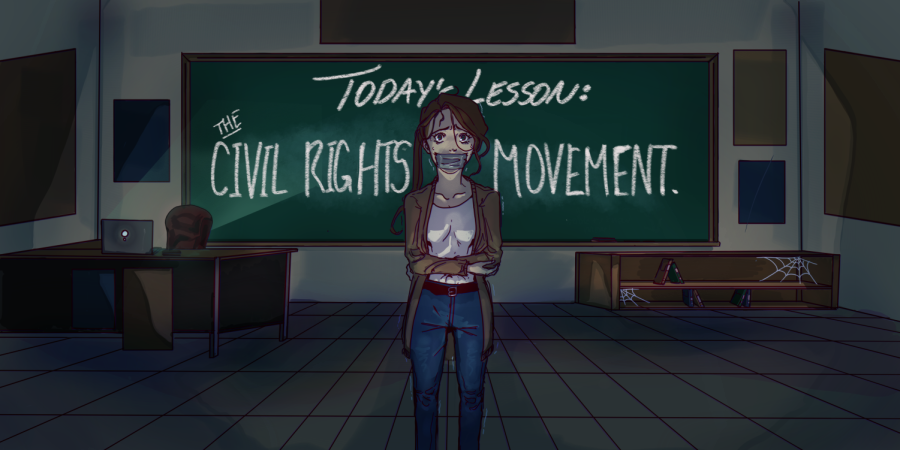

Changes to curriculum have “chilling effect” on teachers

March 18, 2022

Nationwide, legislation restricting how schools teach racism and the history of the United States has made teachers’ jobs more difficult while devaluing students’ education, Jeannie Logan, Social Studies Instructional Supervisor, said.

The Virginia State Legislature has proposed a law curbing teachers’ abilities to discuss topics of race and gender and seeks to avoid “divisive topics” that would make students feel “guilt or anguish” according to the text of House Bill 781, sponsored by Delegate Wren Williams (R-VA).

Logan explained that when schools avoid presenting tough ideas, students lose opportunities to grow and learn because the educational challenges have been removed.

“When we approach education as something that should never make anyone feel uncomfortable, a lot of great learning fails to happen,” Logan said. “I think most people understand that learning and growth often comes through challenge and discomfort, and it’s in those times when our thinking is really sharpened.”

In Florida, the Parental Rights in Education Bill, also known as the “Don’t Say Gay” bill, would restrict discussions about sexual orientation or gender identity in Kindergarten through grade 12, and it would allow parents to sue violating schools, according to the text of House Bill 1557. A removed amendment would have required schools to disclose students’ sexuality to parents against their will, USA Today reported on Feb. 22.

Logan believes that bills seeking to restrict teachers misunderstand the purpose of learning about history, and they are written in a way that would discourage teachers from discussing contentious topics for fear of failing to comply. The purpose of learning U.S. history, Logan said, is to help students understand and be more informed about America and how it operates as a country.

“[These bills] tend to make educators much more reserved and wary of approaching any kind of controversy,” Logan said. “It really does have a chilling effect on what teachers do in the classroom and what they can teach, and I think that’s very unfortunate.”

In addition to changes to school curriculum, book bans have impacted how students learn about racism and other sensitive issues, Helen Holmes reported for The Observer in a Jan. 28 article. Recently banned books include Maus by David Spiegelman, a graphic novel about the Holocaust, which was removed from a Tennessee school district. In a Missouri school district, The Bluest Eye by Toni Morrison, a young girl’s story of racism in Ohio, was banned.

Banning Maus and The Bluest Eye removes books that uplift overlooked voices and stories, David Adamji, English Instructional Supervisor, said. Losing stories that cover difficult topics or historical events deprives students of an important educational opportunity, Adamji said.

“Our job as public high school English teachers is to ensure our students are aware of the truths that shape the human condition,” Adamji said. “Banning books prevents our students from accessing these truths.”

Books dealing with race, sexual orientation, or gender identity are consistently the most challenged and banned books, according to an annual list compiled by the American Library Association. Depriving students the opportunity to learn about different identities can make it harder for students to learn about themselves, Interim Principal Dr. Rosanne Williamson explained.

“Students might be questioning or looking for information as they’re exploring their own identity,” Williamson said. “A lot of identity development happens in high school, and is access to more information helpful to students as they form that identity? Absolutely.”

Illinois has pursued changes to its history requirements through the Teaching Equitable Asian American Community History (TEAACH) Act, bill sponsor Jennifer Gong-Gershowitz, State Representative (D-IL), said.

The act will better include Asian American contributions to American history and contrasts from legislation in Florida and Virginia by not seeking to control or restrict pieces of information about real history and real issues, Gong-Gershowitz said.

“[The Virginia and Florida] bills seek to erase uncomfortable history and silence voices that speak a truth they don’t want to hear,” Gong-Gershowitz said. “The TEAACH Act does the opposite. It shines a light on seldom-discussed but important parts of American history – the good and the bad.”

Efforts to change curriculum are part of a national debate on the identity of America, and highlighting the differences of the United States rather than hiding them makes a student’s education better, Logan explained.

“[The TEAACH Act is] showing [students] what it means to live in a very diverse, multicultural democratic society,” Logan said. “[Society is] made up of all these different groups of people who have all played a role. We all have a story that is really important to the overall story of America.”