Microaggressions demonstrate lasting power of words

March 15, 2019

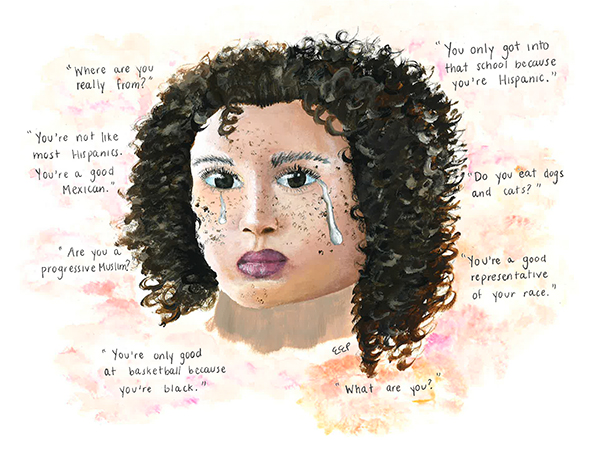

“Where are you really from?” “Wow, you speak good English.” “You’re stealing our jobs!” “You’re not really Asian.” “Go back to your country.”

All of these statements are examples of racial microaggressions, or small comments that subtly or unintentionally display prejudice towards a certain marginalized group, according to Andrea Ball-Ryan, co-sponsor of Black Student Union (BSU).

“Words stay with people,” Ball-Ryan said. “A flippant comment I might make and never think about again is staying with a person for years, because it was about their identity…they are now confirmed to how other people see them.”

Emily Ekstrand, sponsor of Students Organized Against Racism (SOAR), says that microaggressions, though small and unintentional, ostracize and exclude people, and can have a great impact.

“Microaggressions…are little but not insignificant things that are said or done, ways people are treated or talked to that signal to the victim or the recipient that they are somehow different or unwelcome,” Ekstrand said.

Junior Yasmeen Mohammed Rafee was sitting in her Pacific Rim class last year when she heard two boys make fun of the ethnicities of the people whom they were studying. According to Rafee, they made offensive comments in an attempt to be funny, including a remark about Indian taxi drivers.

“As a brown person, that hurts,” Rafee said. “We need to be able to distinguish between humor and ignorance.”

Senior Kathy Yoo says that people have made fun of her ethnicity very directly, and that although people make these remarks to be funny, to the person on the receiving end, they are anything but humorous.

“In class, I remember some guy…taped the sides of his eyes and [said], ‘Do I look like you?’” Yoo said. “I think he thought of it as a joke but [I thought], ‘It’s not funny, why are you [doing] that?’”

Freshman Noor Husain was the target of a microaggression aimed at her religion. When Husain was at the bus stop with friends one morning, one of them made comments about how Muslim girls don’t like when other girls wear revealing clothing, Husain said. According to Husain, she was shocked by the comment.

“He asked me, ‘Are you a progressive Muslim?’” Husain said. “‘You know, one who doesn’t bomb areas or push gays off of bridges?’ It made me really frustrated….I’ve been able to stay strong through it, but it has made me really question [myself].”

Senior Carolyn Castroblanco says that she has faced several racist encounters in different situations because she is Hispanic, including at work and among her friends. She says that many people don’t expect her to be good at academics and assume that she only earns things because she is Hispanic.

“Some of my friends, whenever we started talking about colleges, would [say], ‘You’re going to get in here because you have Hispanic privilege,’” Castroblanco said. “‘You’re not really smart; you’re just Hispanic’…like I was abnormal for being good at academics, [which is] really driving home the point that I’m not supposed to be smart or I’m not smart….[People have also said], ‘Oh you’re not like most Hispanics you’re a good Mexican…You’re one of the good ones.’ I’m not Mexican.”

Junior Raelyn Roberson, co-president of BSU, has had several experiences in which people have credited her physical strength to the fact that she is black. According to Roberson, when she was a freshman, people would also be surprised when she would walk into honors classes.

“At first I kind of just threw it off,” Roberson said. “But now, the more that it happens, the more I’m vocal about it, especially since there’s clubs like BSU and they’re starting to do panel discussions about equality at the school.”

Sophomore Cathy Choi says that she faces stereotypical racist comments such as people asking if she eats cats and dogs, or misidentifying her ethnicity. According to Choi, people assuming she is Chinese or Japanese without knowing that she is Korean angers her because she feels as if her identity is being erased.

“I didn’t really take the fact that people called me Chinese too kindly because I was, and still am, really really proud of being Korean, and being called a different ethnicity entirely, for me, [is] taking away a part of my identity as a person, and that made me really mad at the time,” Choi said. “I would [say], ‘How dare you?’ or, ‘I’m Korean. Why are you calling me Chinese?’…Most of the time that kind of gross over-generalization of someone’s ethnicity or nationality comes really easy to people.”

Yoo says that in the past, she has tried to be “more white” and reject her ethnicity to try and fit in better and avoid potentially racist comments.

“My sophomore year and freshman year…I tried to act more white [and] Caucasian to not make anyone focus on my ethnicity,” Yoo said. “But it never works out because [I’ll] never be white.”

Castroblanco says that she also used to avoid any part of being Hispanic in order to fit in better. She says that in sixth grade she started taking French instead of Spanish because she didn’t want people thinking she had an unfair advantage in the class, even though she didn’t speak Spanish at home, as only her dad is Hispanic.

“For a while I would downplay anything about me that was different, that wasn’t like the majority of my white and Asian friends,” Castroblanco said. “But I realize that was pretty stupid, and it was like hiding a part of myself that everybody else could see…These last two years I’ve gotten more accepting of the fact that I am Hispanic.”

Senior Yulissa Gonzalez believes that many people make racist remarks because they don’t know that it’s wrong, and they’re just saying things without the intention of being rude or offensive.

“They don’t blatantly say racist things, but it’s very subtle and most people don’t pay attention to it, [so] you don’t even know that it’s a microaggression,” Gonzalez said.

Ball-Ryan agrees with Gonzalez that microaggressions stem from ignorance or misunderstandings.

“A lot of it just comes from a lack of understanding and a lack of knowledge,” Ball-Ryan said. “I don’t know that the majority of people are ill-intentioned or trying to intentionally be harmful. I just think sometimes it requires a different level of knowledge that they may not have.”

According to an article written by the Concordian, microaggressions, and the generalizations that accompany them, begin a pattern of alienation, which leads to prejudice, makes way for discrimination and a much more dangerous cycle.

Florence Yee, of the Concordian, writes, “Racism operates on a spectrum, and all of it matters. Its more extreme versions do not appear out of nowhere. Quite like Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, racial violence builds itself on top of its smaller forms. Once a part of the pyramid is normalized and accepted by a dominant group, a higher part starts developing.”

Castroblanco says that people make these comments because of dissatisfaction in their own lives, and because they want to blame their situation on other people.

“If people think that they aren’t going to do well, then they need to find a reason why that isn’t a fault of their own,” Castroblanco said. “So like if I got [into a college] and they didn’t, it would be because I’m Hispanic, not because I’m in any way, shape, or form a better applicant. It seems just a projection of their own insecurities manifested in the form of racism because I’m different than a lot of my friends.”

Ekstrand says that the school has been doing better about addressing microaggressions. According to Ekstrand, responding to discrimination has to be taken as an opportunity to educate instead of punishing students. SOAR’s idea of training students to respond in the moment is the best line of defense, Ekstrand says.

“I think the best line of defense is students standing up to students and helping other people out,” Ekstrand said. “Kids of this generation are savvy and they’re paying attention to social issues, so I think there are students who are aware and who are wanting to stop this.”

Gonzalez is excited about the initiatives that South is taking to combat racism and microaggressions. She agrees with Ekstrand that clubs such as BSU and SOAR are helping the students become more aware.

“GBS students are becoming more aware of racism and microaggressions in the community,” Gonzalez said. “There are many clubs like BSU and SOAR that are talking about when to point [microaggressions] out, and that it’s never okay to say these things. I think it’s really cool that students are becoming more aware of what’s going on and how words can hurt people.”

Husain also believes that one possible solution to microaggressions is simply awareness.

“I think it needs to be spoken about more,” Husain said. “At least an assembly, a get-together…it needs to be presented in a way where people are going to start bringing awareness to it. Whether you’re a different race, different religion, different sexuality, gender, etc.”

Choi believes that microaggressions can be reduced if people think about their words before they speak and keep their assumptions about others to themselves.

“The first thought that comes to your mind, is what you’ve been trained to think of,” Choi said. “But if you make the conscious step to take in a second thought and say, ‘That’s not right. I’ve learned better’ or, ‘I shouldn’t assume things immediately,’ that second thought is what you’re trying to learn, and that’s admirable.”