Chronic illnesses pose threatening obstacles

March 15, 2019

In sixth grade, senior Anna Shabelman started to experience recurring fevers. These fevers would happen every four weeks and according to Shabelman no one could figure out why. Eventually blood tests to determine the cause for the fevers revealed another issue: decreased kidney functioning. This was just the start of Shableman’s chronic health issues.

Chronic illnesses, according to the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), are defined as conditions that last one year or longer that require continuous medical attention or limit activities of daily life. Research from the CDC found that six in ten adults in the U.S. have a chronic disease, and four in ten adults have two or more. Similarly, Health Teacher Christina Zagorski notices this commonality amongst students. According to Zagorski, the health curriculum dedicates an entire unit to noncommunicable diseases like chronic illnesses, culminating in a project.

“Students that [we] are sitting in class with every single day have some non communicable diseases,” Zagorski said. “The more that students are educated about [chronic illnesses], the more they understand what their peers are going through and the more sensitive they can be of things that might come up.”

While Shabelman’s kidney functioning continued to decrease, she found it hard to manage school and take care of herself at the same time.

“I knew that I had an excuse to miss school and work but at the same time I felt guilty about it because I didn’t have a diagnosis [yet],” Shabelman said. “When I would be sick and have fevers and feel horrible, I knew that that was because of my chronic illness but no one else did.”

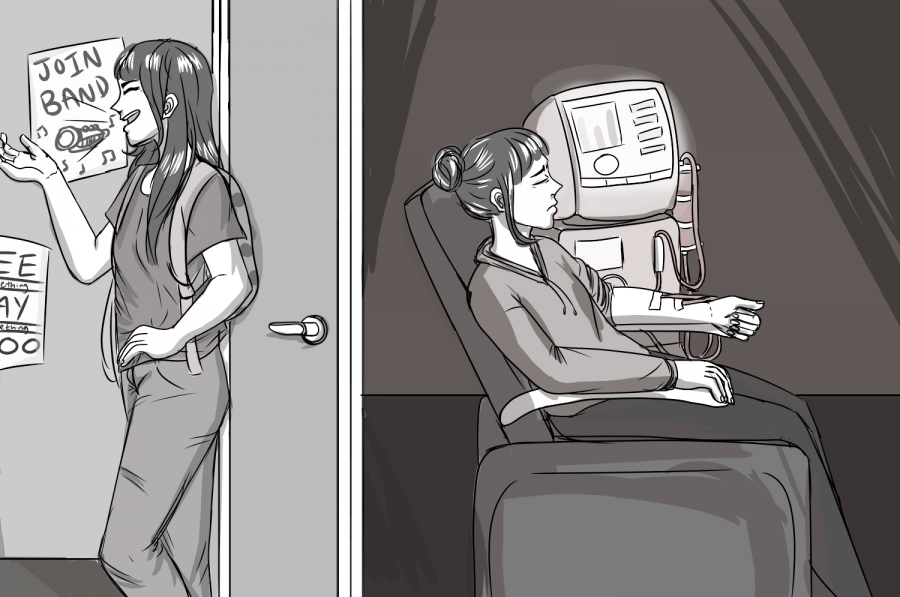

February of her sophomore year, Shabelman went into kidney failure. According to Shabelman, she was in the hospital for about 2o days where she had to start dialysis, a process that is used to remove waste and extra chemicals from the blood. At first, Shabelman said that she started with hemodialysis three times a week at a hospital but then switched to peritoneal dialysis at home every night for nine hours.

“My life turned around,” Shabelman said. “It halted. Everything you put in your body when you are not dialyzing is poisoning you. The idea of being claustrophobic in your own life is really scary. You don’t have freedom or you will die, and those are the only two options.”

After 12 months of dialysis, Shabelman found out that she was approved for a kidney transplant in February of her junior year. According to Shabelman, her uncle, the first person tested, was a perfect match and they were able to coordinate a date very quickly.

“Recovery was horrible,” Shabelman said. “I got transplanted April 9 and I started feeling better April 27. After April 27, I was feeling so good and I [started to] have more freedom to do what I wanted.”

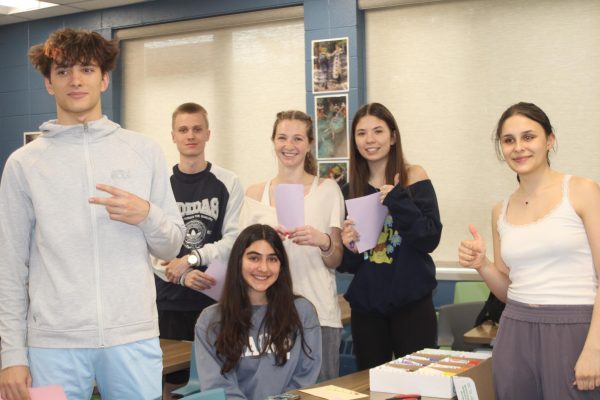

While going through kidney disease, Shabelman said she learned that everything was relative, and that you never know what is going on with other people. As a result of her disease, Shabelman was able to meet junior Safa Mohammed, who has chronic gastrointestinal health issues. According to Mohammed, Shabelman reached out to her through social media, and the two were able to relate to each other very quickly.

“[Shabelman] explained her story and we [found out] we were in the same hospital, had the same nurses and were on the same floor rooms away from each other,” Mohammed said. “We were able to relate to each other’s problems which is a good thing. To have someone who could relate so much, maybe not exactly because we have different conditions, but to still understand what each other is going through [is really nice].”

Mohammed first started to experience gastrointestinal issues in the second semester of her freshman year. Then, at the end of her first semester sophomore year, Mohammed was diagnosed with Superior Mesenteric Artery Syndrome (SMAS), a chronic digestive condition. Mohammed said that she struggled to balance her social life with her condition, especially when hanging out with friends.

“When I was going through my really rough period where I couldn’t tolerate any food, going out was rough because it was weird that I wasn’t eating,” Mohammed said. “I wasn’t ready to tell my friends what was going on because it was something very personal and I only wanted my family, myself and my doctors to know.”

After her artery collapsed, Mohammed was homebound, unable to come to school. According to Mohammed, her chronic illness began to take a toll on her mental health, as she missed her friends and school.

“When you go through a very invisible chronic illness, it does have an effect on your mental health,” Mohammed said. “That’s when the mental and physical health start to blur. You don’t have a social life, you can’t go out with friends, participate in sports, or any other club or activity. At the end of the day, I’m just a regular high school student who has an invisible illness that no one knows about, or some do know about it but can’t see. The only person who can see it and feel it is me.”

As she has recovered, Mohammed explained that she has begun to be more open with what she is going through and has learned to be more appreciative.

“I’ve had so much time to heal and reflect on what happened to me and what happened to my family, [and] how they coped with my illness,” Mohammed said. “I am [also now] really appreciative of everyone [because] you become so appreciative for the small things you have in life. It’s really fascinating to see how so much can be taken away from you in such little time, and then it is restored with certain limitations.”

Similarly, Shabelman stated that after she came out on the other side of her illness, she realized how much her thinking has changed. Shabelman explains how she has been more open about what she has gone through and wants to advocate for others.

“Last year, I thought that [my chronic illness] did [define who I was],” Shabelman said. “I’ve learned a lot about myself. I’ve also learned to accept that it’s okay to have [a chronic illness] be a part of your life. It doesn’t need to define you, but you can recognize it and not be afraid of it. You never know what people are going through. Remind yourself to be accepting of others, even if you don’t know what anyone else is going through, be nice for the sake of it.”