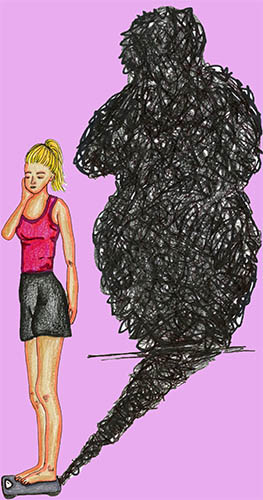

Stress of unrealistic body ideals manifests in eating disorders

Illustration by Riley Gunderson

December 22, 2017

“Slim down.” “Finally lose those last 10 pounds.” “How fit are you?” These magazine headlines encapsulate the unrealistic body standards imposed on today’s society. According to The National Association of Anorexia Nervosa and Associated Disorders Inc. (ANAD), thirty million people of all ages and genders suffer from an eating disorder in the U.S.

According to ANAD, anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge eating disorder are the most prevalent eating disorders. Anorexia is characterized by not consuming enough calories and a dramatic drop in body mass, while bulimia is defined by recurring episodes of binge eating followed by self induced vomiting and extreme exercising. Finally, a binge eating disorder is distinguished by repeated excessive eating.

Senior Kacey Hummel* says she has struggled with body image issues and an eating disorder since she was in middle school. She explains that throughout middle school she realized there were many aspects of her appearance that were out of her control, such as her glasses and braces. However, she felt that she could control one: her weight, by restricting her food intake.

“The one thing I could have control over was food, and that kind of started a toxic relationship with food, and I started looking more online and seeing different pictures of girls or guys that had differing body types than my own,” Hummel said. “Suddenly, I visualized me in that position and I wondered what it would take me to get immediate results to get something like that.”

Social worker David Hartman explains his role in the building is to connect students dealing with various personal issues to outside resources within the community. He says he believes the environment students are in force them to think they must act and look a certain way, especially in how their body compares to their peers.

“I think that our community is a highly pressurized community, and sometimes that gets manifested for women in [an eating disorder],” Hartman said. “Too often it gets manifested in women in [their physical appearance].’”

Feeling these same pressures Hartman describes, Hummel took it upon herself to try and mimic unrealistic body standards present in society. She began to explore various ways to limit her food intake.

“My search history would just be different ways to lose weight,” Hummel said. “I remember having reminders on my phone that would remind me ‘don’t eat,’ or ‘don’t eat this [food].’ I would go to Walgreens and pick up stuff from the diet section, even though I wasn’t on a diet. I would bring in cash so that my parents wouldn’t be able to see what it was [I was buying].”

Senior Rose Dunphy* experienced a similar situation to Hummel throughout her sophomore and junior years. In her sophomore year, Dunphy was formally diagnosed with anorexia nervosa. She explained that on an average day, she would go about twelve hours between meals.

“In a typical day, I would get up in the morning and eat a hard boiled egg for breakfast and then I usually skipped lunch,” Dunphy said. “It would be about seven in the morning until about seven at night was when I would eat again. It was tricky because I had to look normal when I was eating in front of my parents, so [I would usually just eat] whatever they would make [for dinner], but about half of it.”

During her sophomore year, Dunphy sought help for her eating disorder through a therapy center within the community. Throughout her three week partial hospitalization treatment, Dunphy attended group therapy with other struggling adolescents from 8:00 a.m. to 3:30 p.m. While attending the center, she explains how her eating habits drastically differed from her usual routine.

“In the facility, [my food intake] was about five times the amount that I was eating before,” Dunphy said. “We would eat a regular sized breakfast [of] a bagel [with] cream cheese, cereal, an apple and orange juice. Then two hours later it would be snack; then it would be a lunch and they would bring in something from Corner Bakery [with] a yogurt, chips and some mac and cheese. Then I would have a snack again and then I would eat dinner, then another snack after dinner.”

After the conclusion of her junior year, Dunphy did not feel that her eating habits had substantially improved. During the summer going into senior year, she went to a more intensive center for care where she stayed overnight for a month, attending similar therapy to the previous center. At this facility, she had an epiphany after learning about another patient’s lifelong struggle with healthy eating.

“There was a woman in [the residential facility I stayed at] and she was about forty-five-years-old; she was emaciated [and having severe problems with eating],” Dunphy said. “We were in group therapy one night and she broke down and began talking about how she had all of these grand ideas for her life, but how they had all been ruined because she was just in and out of therapy. [In that moment] I realized I did not want to be there in forty years, so after that I started finishing all of my meals, I was completely compliant [and] I wanted other people to have that moment [that I had] where [they realize], ‘What I look like doesn’t have any effect on what I can do.’”

According to Health Teacher Kelley Oziminski, health classes at South make sure to emphasize healthy eating habits and talk about when those habits can become too extreme. Oziminski explains that a block is devoted to this lesson, and students gain a deeper understanding for why an eating disorder surfaces.

“What we’re trying to help students understand is that healthy weight looks different for every person, so we talk about factors that go into being a healthy weight [like] body type, your gender, your activity level [and] your genetics,” Oziminski said. “When we get to our true healthy body image lesson, we try to focus on what are we impacted by [including] what about society makes us think that there is something that is identified as what is beautiful, or this is what you’re supposed to look like.”

Additionally, Oziminski says that if a student struggles with an eating disorder there are an abundance of resources within the GBS community in order to support them.

“[There are many] resources [such as] trusted adults in the building and I feel like we [as health teachers] drive that home because we want students to know there are plentiful resources here and that adults in this building are here to help kids,” Oziminski said.

An example of a resource available to students is the new club called Support and Awareness for Eating-disorders (SAFE), created by senior Emma Dill. She explained that her goal for the club is to promote body positivity around GBS.

“[Starting SAFE] has helped me [think about] how I can preach [body positivity] to others, but then also turn it inwards on myself,” Dill said. “Also, [it has helped me] realize that the things [people] say, sometimes things like ‘Oh I look horrible today’ or ‘I look like trash’ [have meaning]. I’m hoping [SAFE] is helping people realize that what they say, even if they’re kidding, sometimes they still mean it.”

According to junior Carter Morgan, he has not dealt with an eating disorder himself, but he has had experience supporting friends in times of struggle. He thinks the greatest advice to give a supporter is to always be a source of encouragement in their lives.

“[Everyone] should be careful [and cognizant] of what they say and just see what you can do to help them become and [feel] more positive [about how they view themselves],” Morgan said. “Do what you can to be a good friend to them: talk to them, be nice to them, don’t press them on eating, don’t force them to talk about eating if they don’t want to and just treat them like any other normal person.”

Oziminski believes that as society progresses, ideals of beauty do too. She sees beauty as a fluid concept and that various body types should be celebrated to inspire confidence in one’s appearance.

“Beauty ideals are never concrete and they change and evolve as society changes and evolves,” Oziminksi said. “Different ideals of beauty are accepted in today’s culture. Beauty looks different to a lot of people and people are much more accepting of that and it’s not just this one size fits all ideal that everyone is trying to attain.”

*names have been changed