Male students overcome fashion stigmas, promote self expression

April 21, 2017

You are walking down the GBS hallway, and in a two minute span, you spot 12 people rocking bright colored khaki shorts. When it comes to fashion at GBS, senior Ryan Thompson sees the male population following the same fashion trend: the frat boy look. Thompson explains that this fashion homogeneity creates a fashion in crowd and a fashion out crowd.

“You see the frat boy with the bad curly hair, the trucker hat flipped backward, Vineyard Vines shirt, and it’s not a great look,” Thompson said. “That’s definitely a trend, because at least 50 percent of the school looks like that. So, it’s […] the frat boy look, then there’s outliers.”

Junior Eden JD Kim believes that male fashion at South is so strikingly similar because of the closed off environment. The real world of men’s fashion contrasts sharply with GBS’ tight definition of it, Kim explains.

“Because you see the same people every single day, it’s a group, and it’s a closed setting, there’s very strict norms that are formed,” Kim said. “When people start defying those norms, it definitely draws attention […]. Out in the real world it’s not everyone looks the same. There’s a diversity out there.”

According to Thompson, developing his minimalist style took time. At the beginning of his fashion journey, Thompson was scared to step out of the GBS fashion box because, according to Thompson, gay stereotyping is a huge part of men fashion’s culture. This illusory correlation, Thompson explains, between fashion and sexual orientation can easily serve as a barrier for men to express themselves through what they wear.

“The big connotation that everyone thinks when there’s a guy involved in fashion is ‘oh they must be gay,’” Thompson said. “It’s not a negative connotation, but a lot of people assume that. [When I was first gaining an interest in fashion], I thought ‘Oh god! How do I tell my parents I’m into fashion? They’re gonna think I’m gay […].’ It was a difficult hurdle to get past.”

For junior Nathan Wilson, the pushback he received from peers on his fashion choices wasn’t just focused on sexuality. Once he started coming into his own style, which he describes as mainly “dapper,” peers labeled him as “weird.” To Wilson, the behind your back bullying tactic that guys use when insulting other people’s fashion choices is crueler than when girls do the same.

“Girls can be snarky when it comes to fashion, but guys are a low level of vicious,” Wilson said. “Girls will often openly tell you that they don’t like your fashion, but guys won’t say something to you. […] They’ll sit on the other side of the room with their friends and […] point at you and laugh at you. I’ve heard people muttering […] ‘what the hell is up with the kid in the vest?’”

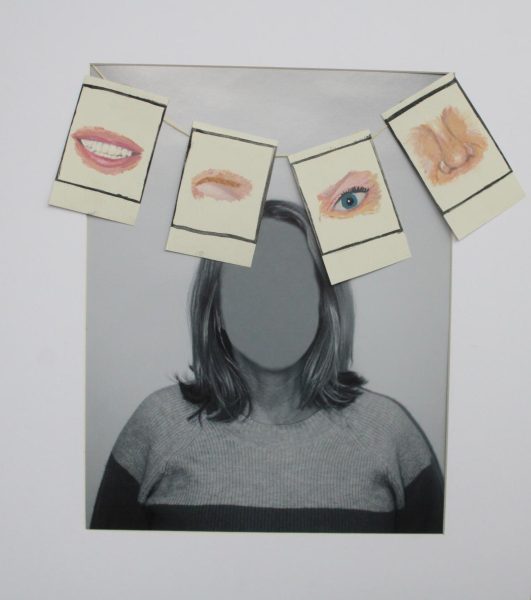

In senior Tony Cipolla’s eyes, fashion shouldn’t even be an element that others critique. Cipolla believes that people make far fetched assumptions about people’s character, sexuality, promiscuity, emotions and interests solely based off what people put on their bodies, when in actuality fashion often doesn’t indicate any of those things.

“My parents always say that I’m trying to create a shock factor with what I wear, which is not true,” Cipolla said. “They ask me what my nail polish means, but does nail polish really have a meaning? It’s just paint on my nail. I wish there wasn’t anything associated with what I wore or what I chose to look like. I wish [fashion] was normalized.”

Judgement is inevitable, so focusing on self-expression rather than people’s perception of your expression is the way to go, according to Thompson.

“[Fashion] should be more what you want to say about yourself […],” Thompson said. “It shouldn’t be what [others’] interpretation of it should be. I’m wearing a Hillary Clinton shirt, which is very subtle, but I’m very liberal. That’s who I am, so I’m putting it out there.”

For Wilson, the way he dresses is an outward expression of his Southern upbringing. Wilson explains that although his fashion has a more Southern feel, he still incorporates activism into his wardrobe.

“[My family] moved here from the South, […] which is why I’m into dressing up […],” Wilson said. “I feel like a fairly formal and polite person, so my image […] tends to sort of mirror that. […] I have a patch jacket, [and] my patch jacket […] has a transgender pride patch, because I used to date someone who was transgender. I want to get a coexist patch for it.”

Sometimes, though, fashion choices aren’t a symbol of political ideas or upbringing, but simply something people like to wear. For Thompson, a scarf that is hated by many is a loved possession in his closet.

“All of my friends are very aware of [my scarf] and sometimes make fun of it,” Thompson said. “It’s this dark red linen scarf. I wanted a linen scarf forever, and it has all these bees and flowers on it. I love it. I’ll wear that with a denim jacket I have, and I just love how it looks.”

According to Wilson, most people that care about you won’t judge your fashion choices, the main criticism just comes from people that aren’t close to you.

“People that make fun of you tend to do so because they feel insecure or they don’t feel the ability to express themselves […],” Wilson said. “Dress how you want to […], [and] most people will envy you for your bravery.”

In all, Kim believes that expressing one’s true self brings a communal positive. The men who are fashion outliers serve the GBS community in a unique way, according to Kim.

“My personal goal in this school is to serve as a role model for those who […] are not the stereotypical girl [or] boy high school student,” Kim said. “I want people to know it’s okay to be different. With that, my fashion kind of plays into that, because people will look at me and think ‘Huh. That person […] doesn’t follow what every single other guy wears, so maybe it’s okay for me to do that too.’”