Marjorie Prime explores unique storytelling

December 18, 2015

What happens when another individual is responsible for telling the story of our lives? Marjorie Prime, a new play by Jordan Harrison at Writers’ Theatre in Glencoe, focuses on this central question. Immersed in the production, I was riveted by some of the best acting I’ve seen on a Chicago stage. Watching these skillful actors, this concept play seemed probing, avant-garde and insightful. Yet when I mulled over the play itself, I began to feel as if the play was nothing more than an interesting thought experiment.

Marjorie Prime is about Marjorie (Mary Ann Thebus), an aging widow with dementia living in the near future. Thebus is heartbreaking and enthralling as Marjorie, and she convincingly depicts the comedy and tragedy of dementia without belittling her character, while always commanding the stage.

As the play begins, Marjorie is provided a “prime”, an artificially intelligent robot that exactly resembles her dead husband at thirty. The “prime” is programmed to tell stories relayed to him by Marjorie’s daughter, Tess (a moving and understated Kate Fry), and son-in-law as if they are his own. He is to be a source of solace for Marjorie as she slowly loses her memory, often seeming almost human until he responds to an unknown question, “I am afraid I don’t have that information.”

In this imagined future, memory is all that tethers us to ourselves and our loved ones. The set is sterile, white and bare; all is transitory, except for the stories we hold on to. Such a world makes memory particularly vulnerable.

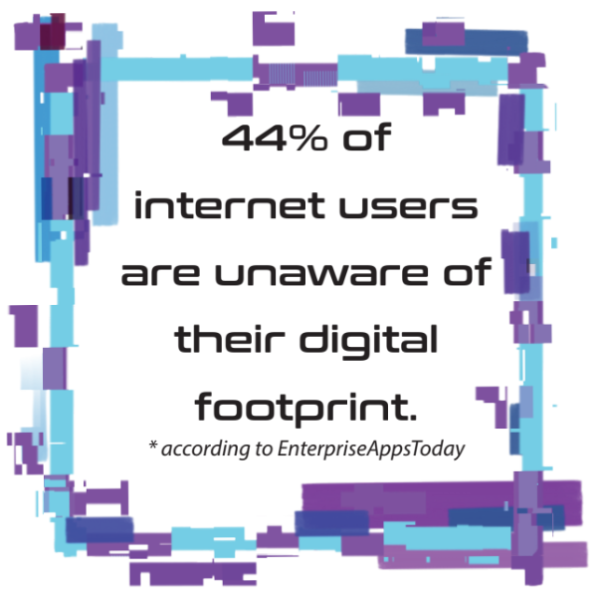

For what happens when someone else is responsible for telling the story of our lives? Are technology and social media more than a way to distort our realities and change our memories, in a way that makes them foreign to us? The idea is as old as Plato’s Cave. Is that not what we do whenever we post a filtered image on a social media site, telling an alternate version of reality, through technology?

These are interesting questions, ones that will perhaps prove prescient as technology increasingly becomes integrated into our lives. Yet instead of examining the questions he poses, the playwright shifts suddenly, focusing less on technology as it relates to today and instead on assertions about the nature of life and death. He chooses more accessible narratives—daughter in a mid-life crisis, marital problems and other life stresses—to get across the alarming message that, without our memories and stories, we are nothing.

The remarkable cast tries valiantly to overcome the glaring unresolved questions of the play, under the direction of Kimberly Senior (one of my own favorite Chicago directors) who gives the actors the freedom to make choices, while still following the natural structure and rhythm of the play.

Still, if you asked this play a question it would respond, “I am afraid I don’t have that information.”