Students discuss illnesses, overcome adversity

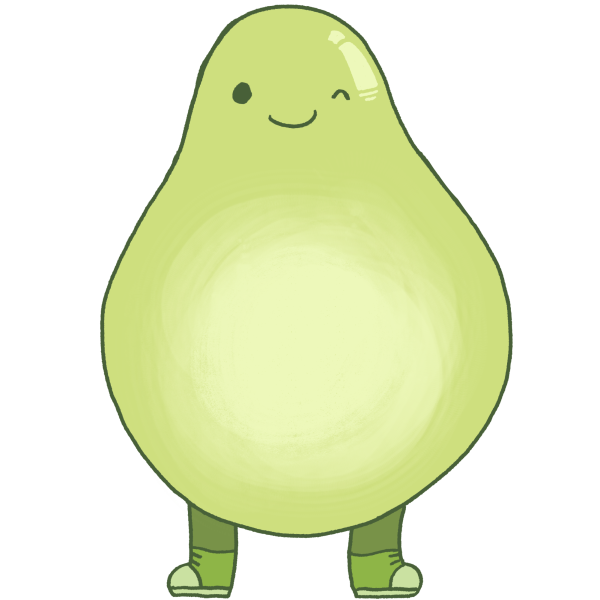

Photo courtesy of Megan Stettler

Standing outside of a cabin at an American Diabetes Association camp in northern Illinois, freshman Megan Stettler (top) and her fellow campers pose with their OmniPods, an insulin management system for type 1 diabetes. Stettler, as well as other South students, has worked to raise awareness and foster relationships with others affected by their illnesses.

April 22, 2016

You are scrambling to finish your in-class essay by the time the bell rings, but suddenly you find your hands shaking so hard you can’t hold the pencil. Unlike your peers scribbling away, your hands shake not from nerves but from the medication you had to take that morning. In your classmates’ eyes, you are just like anyone else, but you know that, like today, your medical condition can affect your life in ways others may not be aware of.

Among the South community, there are numerous students who face chronic medical conditions. According to school nurse Julie Haenisch, the Nurse’s Office works with students who have gastrointestinal diseases, type 1 diabetes, asthma, allergies and seizure disorders, among others.

“I do feel [the Nurse’s Office is] kind of the comfort zone of the school,” Haenisch said. “I am very humbled by the fact that I think students feel safe coming here, or at least I want that to be the culture moving forward. That’s what I believe the Nurse’ [Office] in the building is supposed to be: a safe place.”

One student who utilizes the Nurse’s Office for her medical condition is freshman Megan Stettler. Stettler has type 1 diabetes, an autoimmune disease in which the body is unable to produce insulin. According to Stettler, although she is now managing her diabetes, she initially had difficulties balancing her academics with her condition. Due to her diabetic symptoms, she was exempt from several classes and tests.

“I ended up leaving class so much because […] I always had a low amount of sugar in my bloodstream when I was first diagnosed,” Stettler said. “And so, I would always have to eat a lot of sugar. And you can’t really concentrate. You can’t really do a lot when you’re low, so it was kind of hard to take tests. I ended up not taking a few.”

When she was initially diagnosed, Stettler was wary about informing her friends of her disease. However, once she told them, Stettler found a support group that ultimately helped her control her condition. According to Stettler, this was evident on the eighth grade Washington, D.C. trip when her friends offered to take care of her in case anything were to happen, which was a key factor in allowing her to go.

“My friends are so awesome with [the diabetes],” Stettler said. “Eighth grade year, I really wanted to go on the D.C. trip, and that was like three months after I was diagnosed, which was kind of stressful, but my friends really stepped up. They were like, ‘We’ll give you shots. […] We’ll watch you overnight.’ […] It was really great. I was so happy that they were aware of [my diabetes].”

Similar to Stettler, sophomore Sam Parsons was diagnosed with type 1 diabetes in April 2012. After learning about the condition in his health class, Parsons believed the symptoms he was facing were connected to diabetes. He later was officially diagnosed by his doctor. According to Parsons, the transition into a life with diabetes was made easier with the support he received from his best friend, sophomore Colb Uhlemann, who was diagnosed with type 1 diabetes a year after Parsons.

“It was nice having someone to talk to who actually understood [diabetes],” Parsons said. “Most people […] can’t relate, but Colb can understand exactly what’s going on with me and understands how I feel.”

Even with his supportive friends and stable condition, Parsons admits that he is worried about handling his disease independently while in college, because he will not know anyone that can assist him.

“It is scary having to go off to college without any support, not knowing anyone,” Parsons said. “That’s a little frightening. […] But I’m going to try my best and see [how] it goes.”

Although diabetes is prevalent at South according to Haenisch, it is not the only medical condition among the student body. Sophomore Riley Devens* experiences infrequent seizures, a condition that her doctors believe is temporary. According to Devens, she had her first seizure in eighth grade at home, and since has been optimistic about the possibility of outgrowing her condition.

“I don’t see [my seizures] really as a problem; they will probably just go away on their own,” Devens said. “My dad had a couple seizures when he was little, and [his doctors] just sort of said, ‘Oh [the seizures] are normal, they will go away,’ so [my doctors] are hoping that is what will happen for me.”

According to Devens, she’s experienced seizures at school- twice during her sophomore year. One incident occurred during her math class; after abruptly standing up, Devens fell to the ground in a seizure. Prior to math the next day, Devens was wary of going to the class, but knew avoiding it would not help her situation.

“[My seizures] are temporary, so I like to just think that I should live with it,” Devens said. “I’m not going to let others think that I’m weird for having [seizures]. If they think I’m strange, I don’t really care.”

Some students with medical diseases have also dealt with managing their conditions outside of school, and such is the case with sophomore Hallie Saperstein. Saperstein has ulcerative colitis, an autoimmune disease where the colon becomes inflamed. Saperstein tried to improve her disease by having a fecal transplant surgery, but in her case, it did not work. Rather, the surgery gave her an infection, which required hospitalization for a week.

“This year, I was in the hospital for the first time [because of my colitis],” Saperstein said. “I had a surgery over the summer to get rid of an infection that I had, and I guess [my surgery] did not really work. […] I was really sad and in a lot of pain [in the hospital], especially because the surgery that I had is 99% curable, and I was not cured by it.”

Alongside the surgery, Saperstein used prescribed steroids to alleviate her symptoms. Although it decreased the pain in her stomach, symptoms from her medication spurred new problems. Saperstein felt anxious about her condition affecting her social life.

“I had to go back on steroids [while I was in the hospital],” Saperstein said. “I gained a lot of weight [from the steroids] and broke out a lot too. [The doctors] put me back on [steroids] the week before homecoming, which made me really upset.”

Like the psychological detriments of Saperstein’s condition, Stettler experienced emotional difficulties related to her diabetes. Stettler believes that the media’s lack of differentiation between the two types of diabetes is a main factor in her peers’ misunderstandings. To compensate for this disconnect, Stettler found support by attending an American Diabetes Association camp for teens.

“I’ve met some really cool people through diabetes,” Stettler said. “I went to camp over the summer, and I met a lot of really good friends that I still keep in touch with. It’s so inspirational to see different people living with [diabetes], and it’s definitely changed my mind on different things […] like medical conditions.”

Stettler feels having diabetes has changed her outlook on her life and her peers. With her newfound respect towards others, Stettler believes she is now more empathetic. Her wish is that society can become educated and understanding towards teens struggling with all types of diseases.

“At the beginning of eighth grade, I wasn’t [open about my diabetes], and I slowly just got more open with it,” Stettler said. “I realized [my diabetes is] not something that is negative. Obviously it’s not a positive, but it’s not something that I did personally. […] It’s nothing to be ashamed of.”

*Names have been changed